The American Civil War occurred at a transitional period in medical history when great innovations and life-saving insights were only just becoming adopted by the medical community. The basis of all medical treatment from the 1780’s up until the 1850’s was based on the work of Benjamin Rush, who advocated for the use of “heroic depletion theory” in all medical cases: this meant that the common method of treatment for a variety of ailments always came back to bloodletting, purging or sweating. The root cause of physical maladies was believed to be a humoral imbalance and bringing the body into a state of near crisis would shock it back to health.

Not surprisingly, there were still lingering traces of these purgative methods in use during the 1860’s – in spite of this, many sound, innovative practices were being instituted during the Victorian era that would directly influence modern methods.

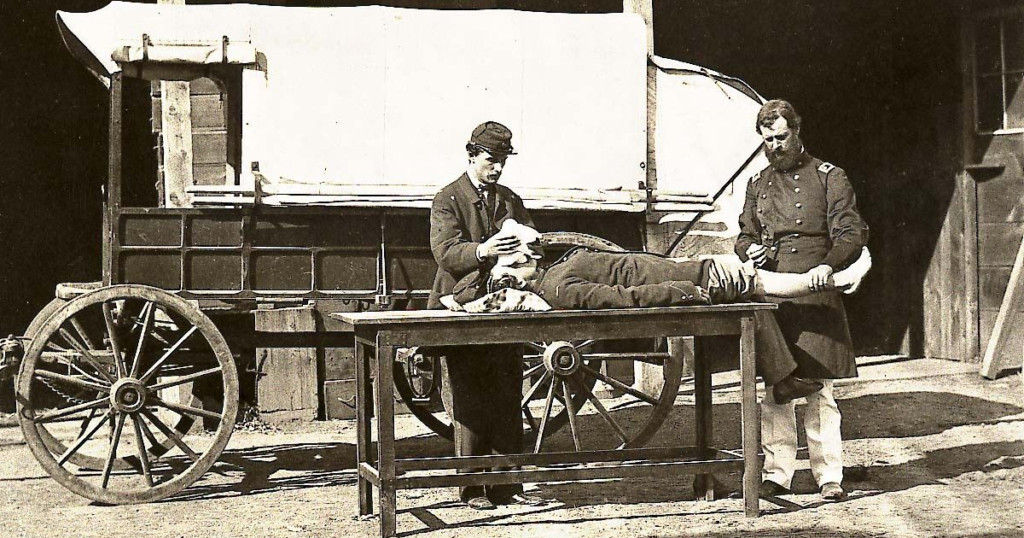

At the Battle of Gettysburg, more than 50,000 men fell as causalities over 6,000 acres, and field hospitals revolutionized the approach to large-scale, emergency care.

And yet the over-arching impression that most people have of the surgeons of the American Civil War are that they were all barbaric, backward and “befuddled with drink”. It’s time to dispel some of these unflattering and incorrect stereotypes. Here are 5 myths about the A.C.W. medical profession that still are widely believed today:

#1. Surgeons were uneducated “butchers”.

While surgeons on the 1860’s were not given the same amount of rigorous training that doctors receive today, they were educated by training directly under a doctor, serving as his apprentice. Generally, training also included a two year stint in a medical college like the ‘Medical School at Harvard’, ‘the Medical Institute of Yale’, ‘the The Eclectic Medical College of Philadelphia and Philadelphia University of Medicine and Surgery’ or one of many others. In a time when standardized didactic training for medicine was not readily available, many would attend additional medical lectures that taught the latest techniques of the day. The Union army became very selective when choosing surgeons, and screened their applicants, choosing them based on skill as opposed to seniority or rank.

In the early parts of the 19th century, the medical arts fell to the women in a household. As the century progressed, the practice of medicine made a shift into a profession which would be populated predominantly (if not entirely) by men. In the past, patients would describe or offer objective data (description of how they felt, sensations, etc) to doctors, but during the Civil War doctors were beginning to make their own examinations of patients and using tool for gather objective data. This included use of auscultation and percussion while examining a patient, as well as some rather modern instruments we still use today: stethoscope, thermometer and microscope. While there would still be widespread use of purgative medications like calomel (“blue mass”), the average surgeon in the Civil War would be picked based on his skill, and educated through hands on experience that would help save countless lives on the battlefield.

“The wounded as they come to the rear, make a person feel sad … My hands and heart full…” 1

#2. Soldiers endured surgery without any anesthesia.

Anesthesia had been first introduced about 15 years prior to the start of the Civil War, and it’s use greatly changed what was possible when it came to saving lives in field hospitals. The ability to give soldiers senselessness to pain would be key in preventing shock, which is often brought on all the faster from pain associated with catastrophic injuries.

There were two types of anesthesia available to surgeons during this period: ether and chloroform. Ether had a tendency to be explosive when it was concentrated into a space through evaporation – the added necessity for candlelight would have made ether a second choice drug while performing surgery. Chloroform was the preferred drug for anesthesia, and it was widely available to surgeons during the Civil War.

This myth pervades partially through first hand accounts from inexperienced witnesses that observed surgery. There are cases of men describing writhing or frantic movements from their comrades who were undergoing amputation. This was not because they were being operated on without anesthesia, but was in fact, a side effect of the use of chloroform. When administered, medical staff would fold a cloth into a cone shape – or a sponge in a specially-made holder – and place this over the mouth and nose of the patient; onto this cloth steady drops of chloroform would be dripped. The goal was to slowly put the patient ‘under’, to avoid shock. While the patient drifted towards unconsciousness, there is a period of heightened movement and speech, called hyper-excitability. For onlookers, this would appear as though the patient were suddenly struggling and trying to speak while being held down by doctors – within a few moments this state of hyper-excitability would cease and suddenly the surgeon would set about his work. The result was that many men would leave field hospitals with tales of terror at seeing their friends struggle while going under the knife. The reality was that it would be extremely rare that a soldier would ever experience amputations without the use of anesthesia.

It is better to employ no special apparatus for inhalation. All that is needed is a common linen handkerchief, on which the liquid is poured. This should be held loosely in the hands of the operator, as in the folded condition it might interfere too much with respiration.2

Valentine Mott, (1785-1865) – Professor of Surgery, Columbia College.

#3. The large number of amputations were a result of poor medical knowledge

The concept of the “Butcher” surgeon is also fed by the data as to the frequency of amputations. Nearly 60,000 amputations happened during the Civil War – a number that would dwarf those from all other conflicts in which U.S. soldiers would be involved. Three-quarters of all surgical procedures performed were amputations.3 The reason for this alarming number was not due to lack of surgical skill, but had everything to do with the type of ammunition used. Modern weapons fire smaller projectiles with higher velocity, causing more immediate fatalities. During the Civil War, the projectiles were far larger, but shot with a lower velocity, causing devastating wounds that wouldn’t be instantly fatal. Surgeons were tasked with resectioning damaged limbs on soldiers that would have been causalities if shot with modern ammunition. When a limb was not healing properly due to infection or was broken beyond repair, it was necessary to remove it and save the life of the soldier.

An example of a surgeon’s kit. Courtesy of the Tennessee Virtual Archives.

#4. Surgeons caused gangrenous infections

In a world without antibiotics or a solid grasp of germ theory, gangrene was ever-present – it was another cause for amputation of limbs. Ganegreen is characterized by discolored skin due to areas where tissue rapidly dies as a result of lack of blood flow caused by an injury or infection. Without a working knowledge of how germs were spread, it was hard for surgeons to foresee how washing a knife in dirty water, or licking the end of a suture before threading it through a needle could corrupt a wound. There was no understanding of how germs could pass from visible clean hands and fingers to wounds – and most bullet wounds would be probed repeatedly with bare hands by several medical staff in the process of acertaining damage and triaging patients. Armed with the knowledge they had at hand, surgeons would work tirelessly through days and nights trying to savage as much human life as they could. Nevertheless, surgeons were quick to observe changes in their patients’ prognosis and often observed small changes that would uncover huge medical breakthroughs.

Union Surgeon Middleton Goldsmith saw that the application of bromide to amputee wounds cut the fatality rate from 46% down to 2.6%. 4 He quickly utilized this new method and published his findings for others to benefit. His work would predate both Pasteur and Lister, making his ability to halt gangrene the extreme cutting edge in medical understanding of microorganisms and antiseptics.

“No tongue can tell, no mind conceive, no pen portray the horrible sights I witnessed.”5

#5. Medications administered by surgeons were ineffective and poisonous.

Doctors and surgeons would use an array of drugs when treating patients – some are still used to this day, such as quinine which was used to effectively treat malaria and Valerian, which was used calm men and help them sleep. About 2/3 of the medications that doctors were using at this time were botanicals. The greatest medication that doctors would impart to soldiers was a standard of sanitation and hygiene that would serve as a necessity when it came to staying healthy in camp.

At this same time, there was readily available a vast number of different “patent medicines”, also called nostrums (from the Latin nostrum remedium, “our medicines”) – these were the Victorian equivalent of our over-the-counter drugs. It was often the patent medicines that were laced with active, toxic or addictive ingredients. The companies producing these medications would often pit themselves against regular medical professionals – their ad campaigns taking on a military approach during the war – warning soldiers of the dangers associated with “the old saw-bones”, “mineral doctors”, and “Knights of calomel and the lancet”.6 Patent medicine peddlers stirred up fear against trained medical professionals and used this to their advantage to sell more of their own medicines through the wildly growing media of printed newspapers. While patent medicines were soon recognized as containing little more than alcohol and opiates and unable to treat just about all of the conditions they claimed to cure, could it be that the aggressive marketing tactics they used to undermine doctors during the 1860’s has continued to shaped modern impressions the Civil War medic?

In conclusion…

While these 5 myths are perhaps based on some scant pieces of truth, they do not do justice to the abilities, ingenuity or human kindness exhibited by medical practitioners during the war. They appeal to our love of gruesome battlefield tales, but do much to underline our overall lack of understanding of Victorian medicine. In spite of grim circumstances and general incognizance as to much of the knowledge widely understood today, the Civil War marked a flash point for many progressive, new methods and treatments. Groundbreaking concepts like triage for causalities was instituted on the battlefield; this was one small organizational shift that saved countless lives. At this same time, the first Ambulance Corp was instituted. Revolutionary new treatments in the battlefield hospitals forged the path for our modern cures.

You cannot imagine the amount of labor I have to perform. As an instance of what almost daily occurs, I will give you an account of day-before-yesterday’s duty. At early dawn, while you, I hope, were quietly sleeping, I was up at Surgeon’s call and before breakfast prescribed for 86 patients at the door of my tent. After meal I visited the hospitals and a barn where our sick are lying, and dealt medicines and write prescriptions for one hundred more; in all visited and prescribed for, one hundred and eighty-six men. I had no dinner. At 4 o’clock this labor was completed and a cold bite was eaten. After this, in the rain, I started for Sharpsburg, four miles distant, for medical supplies .

Dr. Daniel Holt in a letter to his wife, Euphrasia.

- Holt, Daniel M., et al. A Surgeon’s Civil War: The Letters and Diary of Daniel M. Holt, M.D. Kent State University Press, 1995.

- Albin, Maurice S. “The Use of Anesthetics during the Civil War, 1861-1865.” Pharmacy in History, vol. 42, no. 3/4, American Institute of the History of Pharmacy, 2000, pp. 99–114, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41112682.

- Stewart M. Civil War Medicine. Charles C. Thomas Publisher, 1966.

- Goldsmith, Middleton. A report on hospital gangrene, erysipelas and pyaemia as observed in the departments of the Ohio and the Cumberland, with cases appended. Bradley & Gilbert, 1863. Google Books, https://books.google.com/books?id=ZD3zhJ562_kC&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Life and Limb: The Toll of the American Civil War. April 11, 2016 through May 21, 2016, The National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland.

- Boyle , Eric W. “Medical Quackery and the Civil War.” National Museum of Civil War Medicine, 18 July 2021, https://www.civilwarmed.org/quackery/.

Resources:

National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland. https://www.civilwarmed.org/

HISTORVerified

I need convey some questions received through our social media accounts on this piece to the author.

On Myth #2 about operations happening without anesthesia, someone asked if the hyper-excitability described was a feature of the use of ether, not chloroform.

On Myth #5 about doctor’s prescriptions versus patented medicines, weren’t many of the medications pushed by trained physicians also poisonous? Blue mass is mentioned in the article, which contained mercury.

NiobeVerified

Delirium/Excitement is what is called Stage II of anyone going under general anesthesia (historical, modern day, chloroform, ether, propofol, what-have-you). Modern day anesthesiologists can bring patients quickly in and out of this phase as it is dangerous, because of uncontrolled movements, irregular breathing, rapid heart beat, etc.

Cloroform was more widely used as many had already had experiences with the dangers of ether during the Mexican-American War.

Ether was

1. Explosive and extra care was needed both when manufacturing it and administering it,

2. Ether was slow acting, taking upwards of 15 minutes to take effect,

3. More ether was needed to induce general anesthesia than chloroform, and

4. Ether and candle light didn’t mix well, due to it’s flammable qualities, making it difficult to use in an enclosed space/outside of daylight hours.

There were no benefits to carrying or using ether. The main reason it would have been chosen would have been necessity/supply. The risks associated with ether were well known and often linked to tragic accounts from the war. Here’s an account from a young doctor working in a field hospital at Gettysburg: ‘I was trying to secure a large

bleeding vessel just above the inner end of the

clavicle. The only light was 5 candles stuck in a block

of wood, and held very near the ether cone. Suddenly

the ether flashed afire, the etherizer flung the glass

bottle of ether in one direction, and the blazing cone

fortunately in another. We narrowly escaped a

serious conflagration. Why did I not use chloroform,

which is non-inflammable, in conditions well-known

before I began to operate? I fear I must admit to

gross thoughtlessness. My only consolation is that

the patient suffered no harm’.

As for the medicines doctors used, some of these medications would have some basic ingredients that we can now immediately identify as poisonous (blue mass or blue pills basically being mercury and chalk). While this would have had a laxative effect, the side effect would be mercury poisoning. It seems mind-boggling today, but you have to understand that the context of these “medications” were set in a time when arsenic was used in facial creams, wallpapers, dyes – borax was added to sour milk to “freshen it”, etc. There wasn’t a good sense of the possible outcomes of ingesting these substances.