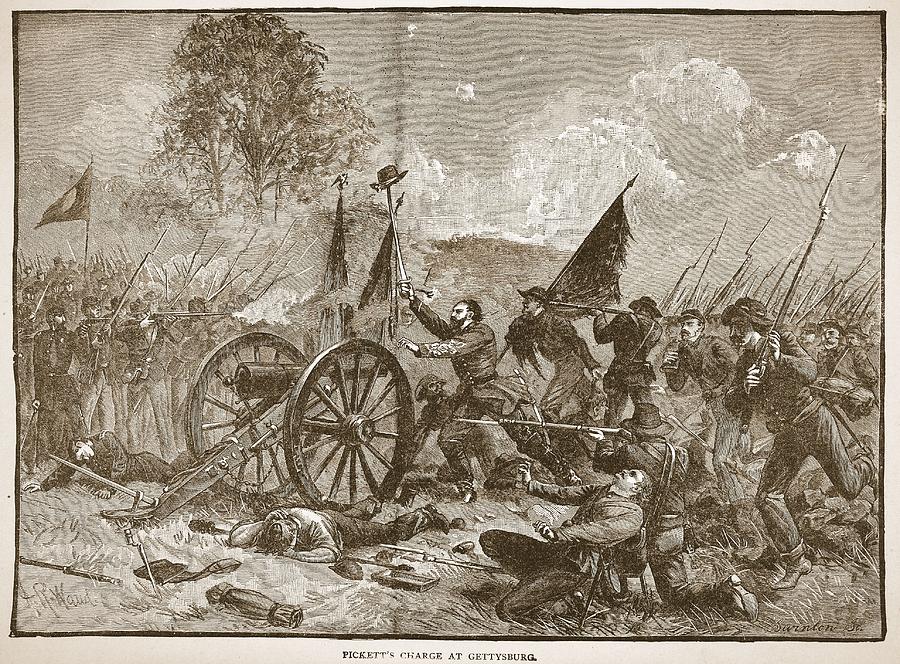

It is a hot July afternoon in 1863 when 12,500 Confederate soldiers begin an orderly and agonizingly slow trek across the open, undulating fields of Nicholas Codori’s farm towards the Union lines. Generals Longstreet and Lee had planned the daring frontal attack, hoping that hitting the Union’s center line would find little resistance. At 2PM, the Rebels stepped out from the treeline and into the open to walk nearly one and a half miles towards the Union lines. The assault itself lasted only an hour, and in that time, Confederate forces would suffer a 50% casualty rate. In the aftermath of the assault, the task was left to Union soldiers to remove the piled bodies, all entwined, dismembered and partially obliterated by the cannons at the minor salient mark now known simply as “The Angle”. In the midst of this grim task, a shocking discovery was made: at the high water mark, where the grisly hand-to-hand combat occurred, the body of a woman was found dressed in the clothing of a Confederate private.

While the event would seem like an anomaly, the reality is that this fallen female soldier was not alone. Through analyzing all the accounts, this phenomena of women in the ranks went far beyond one or two flukes. While this was not the first time that women had donned the identities of men to go to war, what is particularly striking about the Civil War are the sheer numbers of women who enlisted, as well as the relative ease with which they entered this dangerous world.

The unknown dead woman at The Angle was actually one of five women who fought as men at Gettysburg; she was one of two who took part in Pickett’s Charge.1 There were eight women combatants at the battle of Antietam. Six women fought at Shiloh. Distaff soldiers took part at Chickamauga, at the Seven Days Battle and at Fredericksburg; they fought in both the Eastern and Western theaters through four years of extremely bloody conflict. They suffered incarceration in notorious prison camps like Andersonville; and suffered privations and illnesses of camp life. They held ranks ranging from musician to major. “She stood guard, went on picket duty, in rain or storm, and fought on the field with the rest and was considered a good fighting man…” a peer said of Francis Clayton (aka Jack Williams); another gentleman remarked on fellow soldier Rebecca Peterman that she was “one of the most gallant soldiers [he] ever saw… [she] was a good fellow.”2

..

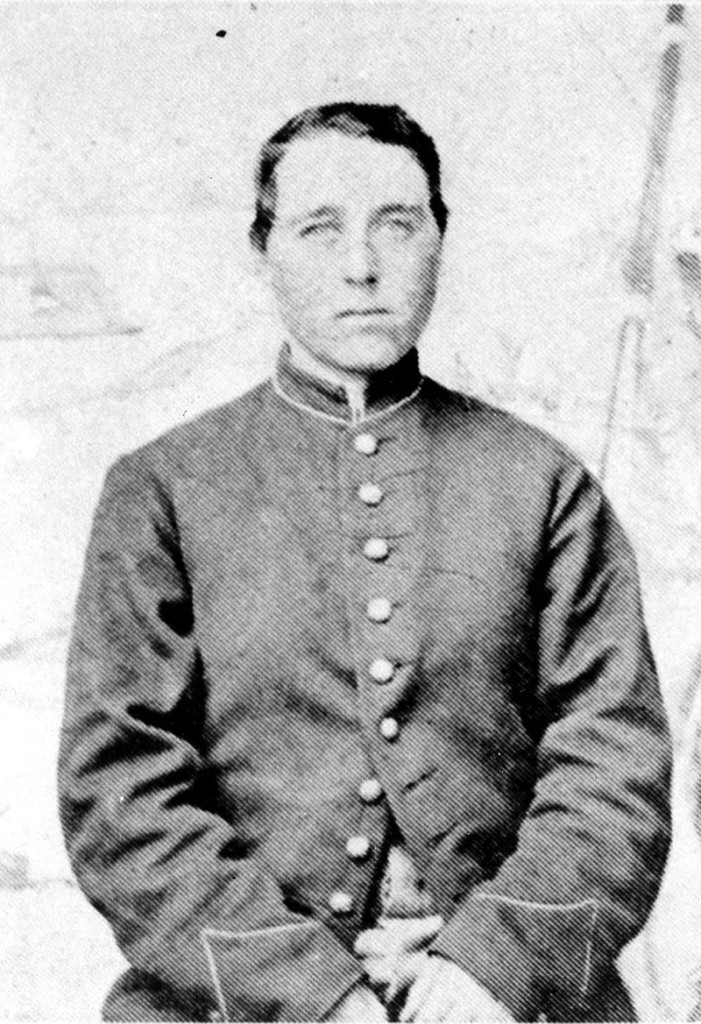

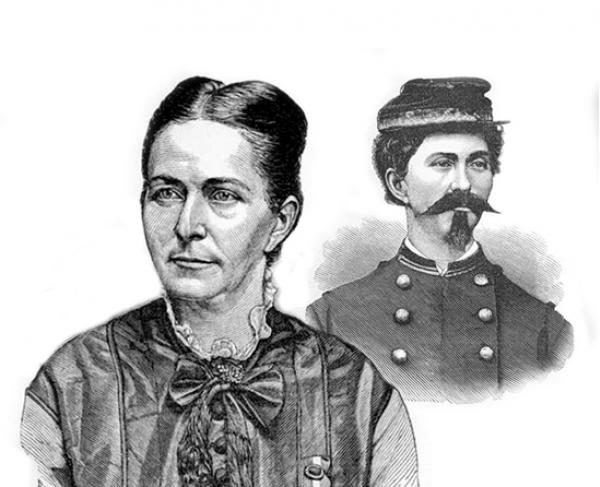

Francis Clayton (also known as Frances Clalin) reportedly joined the army alongside her husband, Elmer. Like many female soldiers, she did not wish to share her story with the public, though newspapers caught snippets of her story along with a few photographs after the war. Much like when a random photo was printed in newspapers and showcased as being an image Ulysses S. Grant, printers were more concerned about profitability than the integrity of Clayton’s story. For this reason, her tale remains shrouded in mystery.3

…

While the prevalence of women in the ranks is not one that is as well known today, it was far more familiar to their contemporaries, as the concept of female soldiers fairly saturated public consciousness during the war. Stories constantly turned up in the press, in poetry, in the gossip bandied about in camp. Two wartime novels featuring disguised women soldiers as the heroines were readily available to stoke the public’s interest; A Lady Lieutenant (published in 1862) even went so far as to inform readers that “[They] may rely upon this narrative as being strictly authentic”.4 Soldiers writing home would tell stories of women combatants found in their companies, newspapers seized upon and trumped up these revelations, officers were duty bound to expel women soldiers who were discovered; soon even high command were apprised of the number of women within the ranks (though they were not always aware of their proximity). Sarah Bradbury (known as Frank Morton), a dragoon, performed escort duty at General Sheridan’s headquarters; when Colonel Henry C. Gilbert raided Beersheba Springs in 1864, five of his thirty-five cavalry troopers were women.5

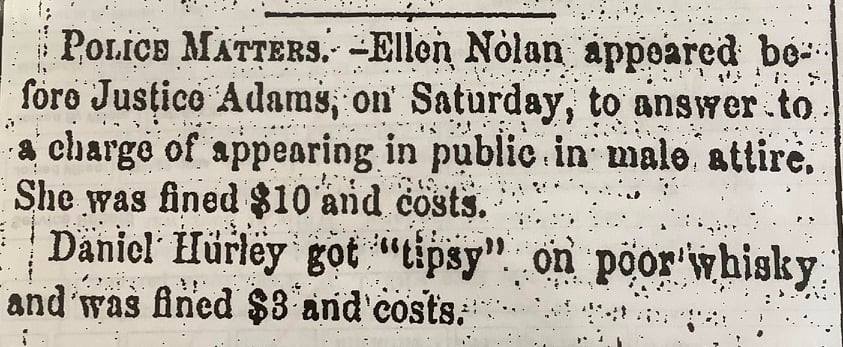

A man from Georgia penned to his wife “There were a great number of fanatic women in the Yankee Army – some of whom were killed…” and he tells her how the grave of one grave is easily found by those curious enough to go looking, as one of her feet stuck out of the ground. A sergeant in the 111th Illinois would write home to his father about a final assault on the Union lines where several Confederate women, including a flag bearer would make a final stand: “They fought like demons and we cut them down like dogs… I saw 3 or 4 rebel women soldiers in the heap of bodies.” A Union soldier informed his fiancee in a letter “We did capture a full-fledged artillery woman who was working regularly at the piece, she was very indenpendent and saucy as most Southern ladies are.” Early on in the war, the Indianapolis Daily Sentinel reported “romantic young ladies of late are frequently found in the military service…”6; later on as the novelty of the occurrences wore off, the tone shifted into a dull recitation of facts: “another female soldier was brought before his honor… yesterday.”7

Regardless of the risks involved, women continued to sign up. Lizzie Compton (aliases Jack or Johnny Compton) was 14 when she first signed up and was kicked out of the Union army no less than seven times on account of what was recorded as “sexual incompatibility”. She served just over a year and a half all said and done, sustaining several wounds. Injury, illness and death were the usual means by which female soldiers were discovered; what is notable is the determination that drove them to maintain their military guise even in dire circumstances, such as when illness swept through the camps or the prospect of starvation met them in prisons. A woman who called herself Alfred J. Luther – a sergeant in the 1st Kansas Infantry – died of “variola” (small pox) and was discovered only after her death. “Poor girl!” a soldier wrote home to his sister about Luther, “who knows what… drove her to embrace the hardships of a soldier’s life… She was as brave as a Lion in battle and never flinched from the severest duties.” While society underhandedly indulged the female warrior motif through the pages of fiction and history, the reality of acting out this archetype in Victorian America brought serious consequences, such as jail time, public humiliation and irredeemable loss of reputation which would adversely impact their future. Sarah Edmonds wrote: “Had I been what I represented myself to be, I should have gone to the hospital…But being a woman I felt compelled to suffer in silence… in order to escape detection of my sex. I would rather have been shot dead, than to have been known to be a woman and sent away from the army.” While the end result of discovery usually would result in expulsion, towards the end of the war, the Confederates would notably not insist their women warriors leave the ranks – the need for men being too great.

‘I can trust you and will tell you a secret. I am not what I seem, but am female. I enlisted from the purest motives, and have remained undiscovered and unsuspected…I wish you to bury me with your own hands, that none may know after my death that I am other than my appearance indicates.’

– Confession of a dying female soldier in the memoirs of Sarah Edmonds

Entering the soldiering life seemed shockingly easy for these women – partially owing to societal mores as well as the overall circumstances of the war. The United States did not have a large standing army at the outbreak of the conflict, so it was necessary for raw recruits to be brought in, educated and drilled in every aspect of warfare, turning them from civilians into soldiers. Men would remain in uniform for months at a time, even sleeping in them, and bathing just as infrequently; the standard issue clothing were oversized, form-blurring garments. There were no documents for identification; it was literally as simple as cutting one’s hair, donning trousers and inventing a male name. While the medical examination would seem like the dead end for many a woman’s dream of being a soldier, too often the enlistees were not required to disrobe. In one case, a doctor simply took the hopeful recruit by her hand and asked “Well, what sort of living has this hand earned?”, after proffering a reply, the examination was over. A young woman only known as “Miss Martin” from Cincinnati was turned away by Union recruiters five times – four of these rejections were on account of her being too short; only on the fifth attempt to join was she asked by the medical examiner to undress. The newspaper that approached her for comment afterwards reported “she says other girls have got into the Army and she could not see why she did not.”

Once their military careers were underway, distaff soldiers would have to adopt a water-tight male persona, carriage and predilections. Some went so far as to don false mustaches and expertly sewed “muscle” padding into their uniform coats. Being men meant that these women shed the social censure associated with their participating in a number of masculine pastimes: drinking, smoking or chewing tobacco, swearing, playing cards and even brawling. Sarah Wakeman (alias Lyons Wakeman) wrote home to her parents “Stephen Wiley pitched on me and I give him three of four good cracks and he put downstairs with him Self.”8

While the number of distaff soldiers that fought in the American Civil War is subject to fluctuation as new accounts are uncovered or existing ones debunked, the number ranges between 400 to 1000. While a statistically insignificant number, they nonetheless fought and suffered alongside their male counterparts. Unlike men, they would not be rewarded for their service, but ridiculed and written off as an anomaly. The novelty of their existence caused generations to trivialize their experiences as soldiers – and the price they paid for overthrowing the rules of society would cost them more than their male counterparts would ever experience.

Though often ultimately misunderstood by contemporaries, the motivations of women soldiers mirrored those of men, and varied greatly: some were personal, some patriotic and some merely practical. Unlike the century before, the “proper” Victorian lady’s sphere had narrowed drastically, even to the point of condemning all forms of work outside of the home.9 For women who needed to earn an income, the options were few and reserved for the lowest positions in the social strata. Sewing, domestic service and prostitution were jobs open to women with no specific skill set. A maid in New York would make as as little as $4-$7 a month – a laundress might earn up to $10 per month.10 On the other hand, 3 months in the army paid a generous $39. The aforementioned brawler, Sarah, a. k.a. Lyons Wakeman had no qualms about dressing as a man in order to seize a $152 signing bounty offered by the 153rd New York Infantry to help pull her family out of debt. “They wanted I should enlist so I did. I got 100 and 54$ in money,” she wrote home, and further instructed her parents to use it and that she would send more as she earned it.

One cause that pushed many to join, was avoiding the separation of themselves from someone who had gone to war. Women soldiers would often initially enlist alongside fathers, brothers, husbands and lovers, but what is curious is that their resolve to stay and fight often remained even after their loved one had died. Joining the army with her husband, Frances Clayton (Jack Williams) watched him die beside her in battle; yet when the command came to fix bayonets, she stepped over his body and charged. Francis Hook (aliases Frank Miller / Frank Henderson / Frank Fuller) had joined the army with her brother, who was her only living relation since they were orphaned as children; when her brother died in combat, Frances continued on with the Army, even changing her pseudonym and reenlisting after being wounded as discovered to be a woman. Sarah Edmonds would later express the sentiment that was perhaps shared by many of her fellow female warriors: “I could only thank God that I was free to go forward and work, as I was not obliged to stay at home and weep.”

They chose to put their lives on the line for a country that by consequence of their gender did not grant them the full rights of citizenship. They chose to risk the legal, financial and social punishment that would be theirs for wearing men’s clothing, let alone taking a the role designated for males. They chose to answer the call of their Country in it’s time of need – to follow the dictates of their conscience or their heart – or to simply embrace opportunities that were constitutionally promised to all, but denied to many. While their stories have been trivialized, sensationalized or largely forgotten, they cannot be denied their place in history as warriors.

And so upon that gory crest

We made a grave where she might rest,

And laid her down with tender hand.

Her woes unknown, unknown her name.

She sleeps upon her field of fame.

No storied page her deeds will tell,

But calm she sleeps and all is well.

– Excerpt from the Poem “A Campaign Incident” by Henry Clinton Parkhurst , based on the discovery of a dead woman soldier.

- United States. War Department. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies. Series 1, Volume 27, In Three Parts. Part 3, Correspondence, etc., book, 1891; Washington D.C.. (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth154599/: accessed October 30, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Government Documents Department.

- Blanton, D. A., & Cook, L. M. “‘Fairly Earned her Apaulettes’ Women Soldiers in the Military Service” in They Fought Like Demons: Women soldiers in the American Civil War. E-book Ed. Vintage Books, 2003. Kindle.

- Chernow, R. Grant. Penguin Books, 2017.

- Wilmer, R. H. The Lady Lieutenant : a wonderful, startling and thrilling narrative of the adventures of Miss Madeline Moore. 1862. Forgotten Books, 2018. Under the engraved plates included in pagination: “Who, in order to be near her lover, joined the Army, was elected Lieutenant, and fought in Western Virginia under the renowned General McClellan; and afterwards at the great battle of Bull’s Run. Her own and her lover’s perilous adventures and hair-breadth escapes are herein graphically delineated. The reader may rely upon this narrative as being strictly authentic.”

- Blanton, D. A., & Cook, L. M. “‘Fairly Earned her Apaulettes’ Women Soldiers in the Military Service” in They Fought Like Demons: Women soldiers in the American Civil War. E-book Ed. Vintage Books, 2003, p. 1327 Kindle.

- “Romantic Young Ladies.” The Daily State Sentinel, 12 Apr. 1862. (https://newspapers.library.in.gov/: accessed October 30, 2021)

- “Another Female Soldier.” The Daily State Sentinel, 24 Dec. 1863. (https://newspapers.library.in.gov/: accessed October 30, 2021)

- Blanton, D. A., & Cook, L. M. “‘Fairly Earned her Apaulettes’ Women Soldiers in the Military Service” in They Fought Like Demons: Women soldiers in the American Civil War. E-book Ed. Vintage Books, 2003. Kindle.

- Lerner, Gerda. “The Lady and the Mill Girl: Changes in the Status of Women in the Age of Jackson.” Midcontinent American Studies Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, Mid-America American Studies Association, 1969, pp. 5–15, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40640814.

- United States, Statistics Bureau (Treasury Dept.). Special Report on Immigration. Government Printing Office, 1871. (https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433007982816: accessed October 30, 2021)

brianstammVerified

Great article. One of the lesser written about subjects of the Civil War.