Across the dinner table on a November evening sits another of William Godwin’s disciples. This one is the heir to a baronetcy, an idealist when it came to the reinvention of society with a wild, unearthly look to him. Mary nibbled at her dinner, listening attentively to the conversation he had with her father. She had arrived home from Scotland the day before and was curious to meet Percy Bysshe Shelley and his well-dressed, young wife. At 14 years old, Mary’s interest was piqued, only in as the young man seemed key to offering financial support to her father.

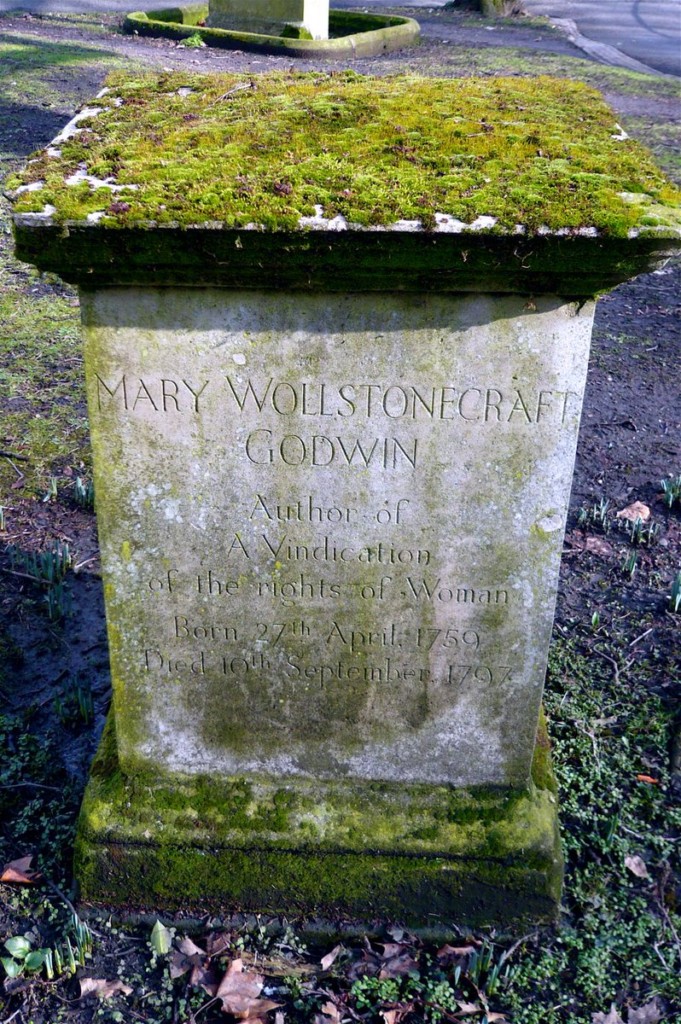

William Godwin was a journalist and philosopher, famous for two novels he penned to counter set political or social injustices. Godwin was an advocate for atheism, anarchism and freedom from the strict social mores of the day. His relationship with the feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft produced a daughter, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin. Shortly after giving birth, Wollstonecraft died of infection and was buried at the St. Pancras Gardens Cemetery – a location that was frequented by Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin through out her childhood. William Godwin (though opposed to the concept of marriage) was quickly remarried to neighbor Mary Jane Clairmont; a woman who, in an attempt to raise the prospects of her own two children, would malign Mary, belittle her and attempt to undermine her education. Mary, who suffered under this harsh treatment with no real intervention from her father, was sent to live with relatives in Scotland for her teenage years. It was during a brief visit home that she first met Shelley.

In 1814, she would meet Shelley again; this time his manner would betray a grinding sadness and failing health due to a nervous condition coupled with supposed tuberculosis. His wife’s (Harriet Shelley nee Westbrook) interest in her husband had waned, in part due to the larger portion of her attention and affection being transferred to her children. Percy and Harriet were married in Scotland, a popular destination for elopement weddings, as the requirement for the reading of the bands in advance of a marriage was not necessary. By the time Shelley was frequenting the Godwin house again as Godwin’s student-patron, he had inexplicably remarried Harriet in England to assure the validity of the union, but by this point Harriet was living separately from her husband. Shelley deeply regretted the “rash & heartless union” he had entangled himself in. Feeling unloved was something Mary could immediately relate to, having lost her own mother when she was an infant and feeling unprotected by her father while enduring how his new wife took every opportunity to mistreat her stepdaughter.

The cemetery is an open space among the ruins, covered in winter with violets and daisies. It might make one in love with death, to think that one should be buried in so sweet a place.

— Percy Bysshe Shelley, Adonais

Mary soon found that she could pull Percy out of his melancholy. In return she had a friend who was constantly churning over new ideas, sharing them with her and actively working to embolden her confidence in herself. Soon Shelley discovered the place where Mary spent so many of her waking hours: at her mother’s graveside. In order to escape her stepmother’s attention, she would visit the tomb stone to read and reflect for hours on end. The Wollstonecraft grave became the backdrop for two of the era’s most illuminated thinkers to exchange ideas. In her, Percy saw his intellectual equal; in him, Mary saw the culmination of her own ideals. It was at her mother’s grave that Mary first confessed her love for Shelley, a date that Shelley marked as the moment of his true birth from that day onward.

Shockingly, William Godwin was displeased when the couple told him of their affection and intentions to be together. In response the pair ran away to Europe, where they could be free from the political and social confines of England. Shelley made the offer for his wife Harriet that she and their two children join them; Harriet refused and the offer was extended to Mary’s step-sister Claire. The enraged Mrs. Godwin would inevitable track down and fetch her daughter home.

1816: The Year Without A Summer

The year that Percy and Mary first fell in love was known as the “year without a summer”, due to the volcanic winter caused by the eruption of Mt. Tambora the previous year in the Dutch East Indies. It was an agricultural disaster for many parts of the world, causing instances of hard frost and river ice to continue into July and August for parts of New England, the Atlantic region and much of Europe.

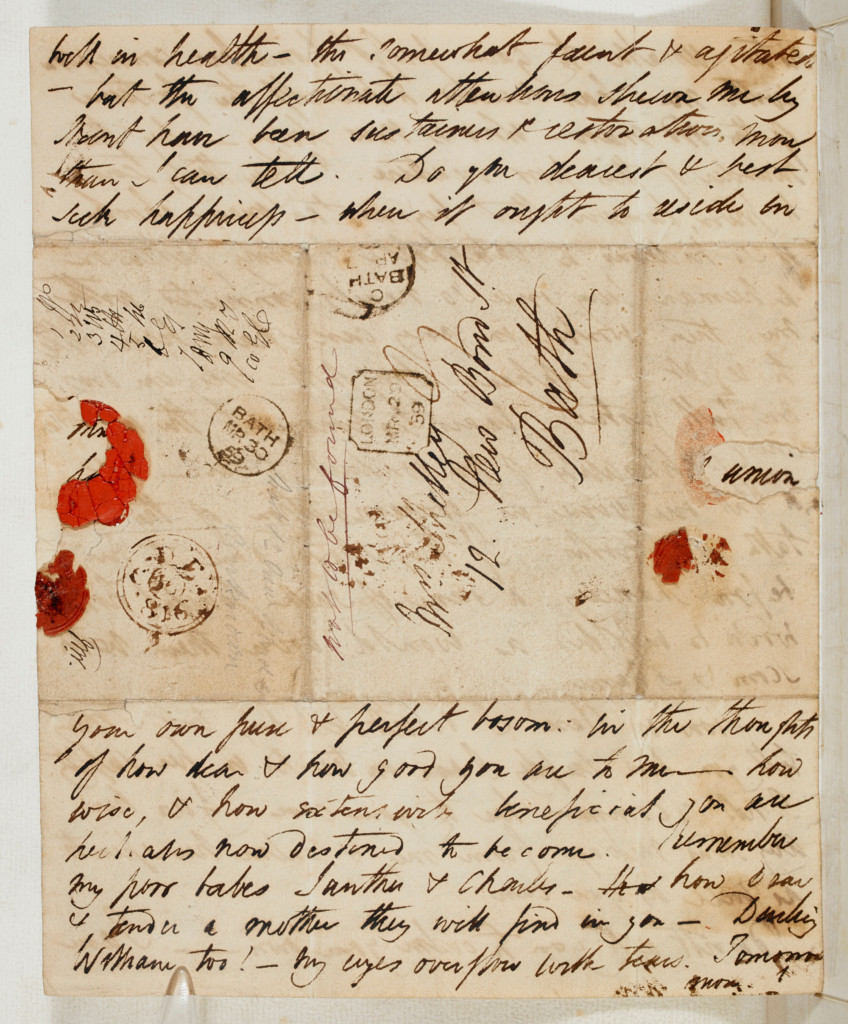

Percy’s affection for Mary endured their forced separation, while Mary was pregnant with their first child. “How hard and stubborn must be the spirit that does not confess you to be the subtlest and most exquisitely fashioned intelligence!” Percy Bysshe Shelley quickly scribbles, “That among women there is no equal mind to yours… and I possess this treasure!” For some weeks he was living in hiding from his creditors. “Why am I not with you? Alas! We must not meet.” While he was the heir to a baronetcy, Shelley has fallen out with his father after being expelled from Oxford for having written radical pamphlets. This caused him to diminished income while supporting a wife, two children as well as the recipient of his written adorations. Her replies always smoothed over the his agitation, “My best love, to you do I owe every joy, every perfection that I may enjoy or boast of…”

In 1816, Shelley’s wife (who was prone to extreme bouts of depression and suicidal ideation) committed suicide by filling her pockets with stones and throwing herself into the Serpentine River. She was reportedly in the advanced stages of pregnancy with another man’s child – after he jilted her, she decided to end her life. Her death deeply affected Percy, who cycled between feelings of loss, anxiety and guilt – though his wife’s death undeniably lessened the financial strain he was under. While Mary and Percy were both philosophically opposed to the institution, they were married after two years of concomitance in order to strengthen his case for receiving the custody of his children by Harriet.

Life and death appeared to me ideal bounds, which I should first break through, and pour a torrent of light into our dark world.

— Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

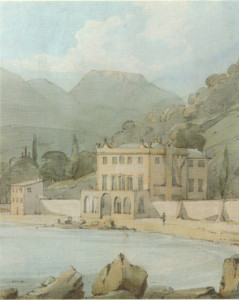

Apart from the brief stay in England to be married, the lovers generally lived abroad, enjoying the company of poets, philosophers and radicals. During a stay with Lord Byron at his Lake Geneva mansion, Mary would first relate the plot line of what would become Frankenstein while the group chatted over breakfast. Their travels would take them to Italy, accompanied by their growing throngs of friends and adherents. Their group of intimates included poet George Gordon Byron (Lord Byron), novelist and adventurer Edward Trelawny, as well as Clair Clairmont (Mary’s step-sister), Byron’s Italian mistress Teresa Guiccioli, Thomas Medway (Percy’s cousin), Jane and Edwin Williams, and journalist Leigh Hunt. Shelley and Byron became avid sailors, causing them to be away from shore for days at a time. It was during one of these trips that Byron and his crew observed Shelley’s boat had vanished from the horizon following an intense storm.

Though the storm only lasted the better part of twenty minutes, the sailors were carrying a dangerous amount of sail while toiling in heavy seas. Another ship risked approaching their small vessel to offer to take the men aboard, but Shelley refused. When the captain yelled to Shelley that he must take in sail or perish in the storm, Shelley stopped Williams from complying. Ten days later, the remains of Percy Bysshe Shelley and Edwin Williams washed up on shore. The “face and hands and parts of the body not protected by dress were fleshless,” so Shelley was identified by his clothing and a copy of Keats’ poetry in his jacket pocket. He was buried hastily in quick lime on the beach.

Due to Italian quarantine laws, Percy Shelley’s body could not remain in the makeshift burial where his friends interred him, so he was exhumed and placed into a iron crematory made specifically for the occasion, described as a “kind of cauldron”, “five feet long, 2 broad… supported by legs two feet high…” Salt, oil and wine was poured over the body to produce a destroying fire. A mattock strike accidentally hit the skull while he was disinterred. His remaining skin was indigo due to the expose to the quick lime. Gallons of wine, oil and salt were poured over the body.

Trelawny wrote: “more wine was poured over Shelley’s dead body than he had consumed during his life. This with the oil and salt made the yellow flames glisten and quiver… the frontal bone of the skull, where it had been struck with the mattock, fell off; and, as the back of the head rested on the red-hot bottom bars of the furnace, the brains literally seethed, bubbled, and boiled as in a cauldron, for a very long time.”

As the poet was burned, all attending recorded how the fire turned the metal white with heat; and that, after his flesh was consumed, the ribs fell open to reveal Shelley’s heart, somehow unaffected by the flames. Edward Trelawny burned his hand rescuing the organ from the pyre, recording the event over and over in his many written accounts of that day: “The corpse fell open and the heart was laid bare… the only portions that were not consumed were some fragments of bones, the jaw, and the skull, but what surprised us all was that the heart remained entire… In snatching this relic from the fiery furnace my hand was severely burnt.” Percy Shelley’s heart would became a relic viciously fought over by his closest friends.

There were quite a few from the Romantic poet’s entourage who felt they should lay claim to the heart, but Lord Byron said that the heart should be gifted to Shelley’s widow (in some accounts, Byron himself also asked for Shelley’s skull). Trelawny handed the heart to poet Leigh Hunt, believing in part that Hunt would deliver it to the grieving Mary Shelley. But in an appalling turn of events, Hunt claimed ownership of the organ, stating his feelings for Shelley overruled “the claims of any other love.” Leigh Hunt had been invited to Italy by Shelley to help him and Lord Byron edit a radical new journal, the Liberal. In a letter to Mary, Hunt refutes Byron’s designation of the heart for her, saying “He has no right to bestow the heart & I am sure pretends to none… If he told you that you should have it, it could only have been from his thinking I could more easily part with it than I can.” Though it seems like a macabre desire to own such a thing, in the 1800’s it was customary. In the end, Lord Byron used his financial leverage over Hunt to procure the heart for Mary.

Upon Mary’s death, Shelley’s perfectly preserved heart was found hidden in her locked writing desk, wrapped in silk and a folded poem written by Percy Bysshe Shelley. Forty years after his death, his heart was buried with Mary in Bournemouth, England.

Death is the veil which those who live call life; They sleep, and it is lifted.

— Percy Bysshe Shelley, Prometheus Unbound

Sources:

Hughson, Shirley Carter. “To Mary Shelley, Octoboer 27, 1814.” The Best Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, A. C. McClurg and Company, 1892, p. 46.

Marshall, Florence A. Thomas. Life and Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Volume I (of 2): Volume 1. Outlook Verlag, 2020.

Bieri, James. Percy Bysshe Shelley: A Biography: Exile of Unfulfilled Reknown, 1816-1822. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2006.

Lovejoy, Bess. “Mary Shelley’s Obsession with the Cemetery – Jstor Daily.” JSTOR Daily. JSTOR, October 3, 2018. https://daily.jstor.org/mary-shelleys-obsession-with-the-cemetery/.

Lewis, Joseph William. “Did They Rest in Peace?” Google Books. Ebook Edition. Accessed April 12, 2022.

Wheatley, Kim. “‘Attracted by the Body’: Accounts of Shelley’s Cremation.” Keats-Shelley Journal 49 (2000): 162–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30213051.

Sheridan, Claire. “Anti-Social Sociability: Mary Shelley and the Posthumous ‘Pisa Gang.’” Studies in Romanticism 52, no. 3 (2013): 415–35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24247339.

brianstammVerified

Very interesting article. Somewhat macabre in the end however it shows the power of love.