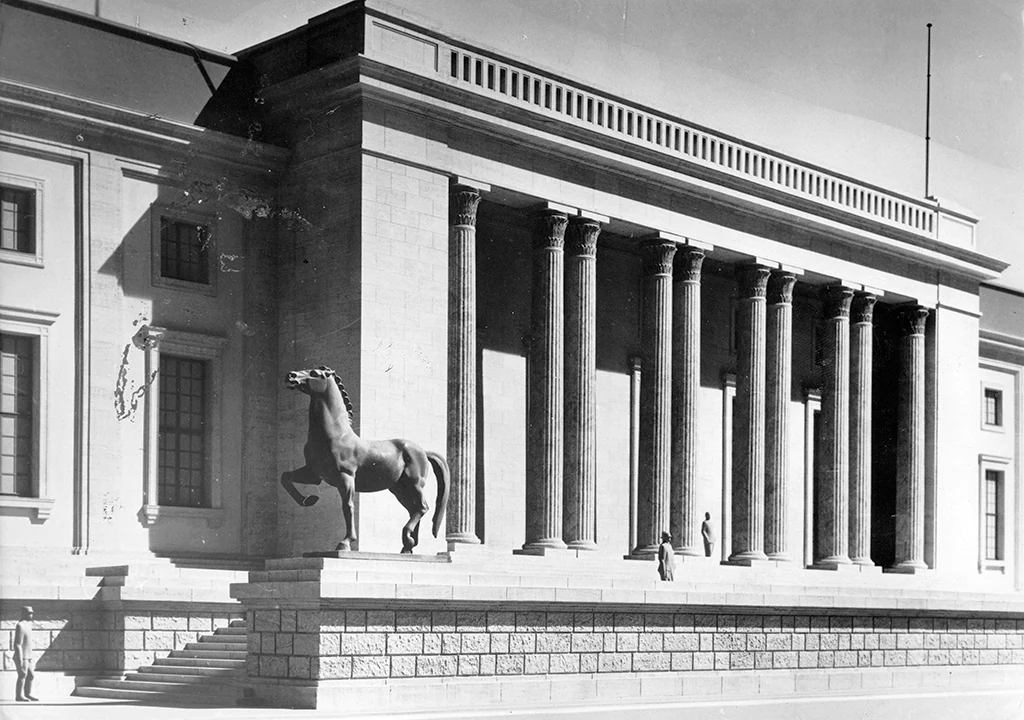

Outside the New Reich Chancellery, artist Josef Thorak’s 16-foot tall bronze Walking Horses stood guard. They were part of a massive installation commissioned by Albert Speer, Hitler’s pet and official regime architect, who was in charge of redesigning the aesthetics of the state to better suit the subliminal propaganda messages those in power wanted to impress upon the population. The horse became a key symbol for the Nazis. The Nazi party would create it’s own mythology, steeped heavily in the equestrian culture of the Knight – and at times, seeming like it was lifted verbatim from a bad science fiction novel – Germany would act on these absurd ideas, leaving suffering in their wake. In a few cases, those standing in opposition to Hitler would intervene before the full impact of the destruction he orchestrated took effect. This is one of those stories.

Hitler’s “Equine Master Race”

In Hitler’s mind, the ideal warhorse was one that in many ways hearkened back to the warhorses of old – the faithful and brave mounts of Medieval Knights. This ideal horse blended the desirable traits of the Medieval destrier and courser into a single, ultimate equine, bred for the battlefield. Inevitably, the callous and quasi-scientific manner that typified many of the Nazi’s undertakings would play out in the quest for the “Perfect Horse”.

So, why were horses so important to the Germans? The reality of World War II was that Germany was not the fully mechanized nation that is often portrayed in popular narratives. The concept of the Tiger tank or automatic machine gun outclassing the Allies – a popular trope in movies and fictions about the war – was not really a part of the German war mentality at the time. While Britain espoused the concept of “Steel not Flesh” as a push to depend more on technology and machinery instead of horsepower, Germany possessed a vast army that was only 10% mechanized and far more reliant on horses and men moving on foot.

Film clips of tanks and trucks bringing troops into battle were the ones that were preferred for Nazi propaganda news reels – and were reused over and over in order to hide the truth that Germany lacked the mechanization of their enemies. During the invasion of France, the German forces behind the Panzer division consisted mostly of horse-drawn wagons – their advance was so slow in comparison to the tanks that the advance was ordered to halt for fear of being cut off from the infantry and supplies lines.1

By 1938, Germany’s army was dependent on the 180,000 horses and donkeys they utilized as part of the everyday logistics of battle — and their demand of horseflesh was only increasing as the war went on.

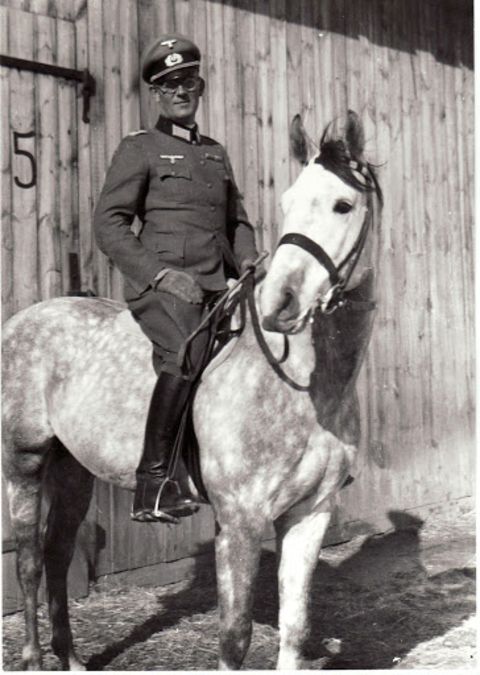

The horse was a creature that held a good deal of symbolism for the German leaders who were attempting to ennoble the simple, honest attributes of the völkisch movement. This movement was part of a general fixation on folk life in the face of a mechanized, modern world. Hitler had, in one of his more antithetical propaganda campaigns been portrayed as a Teutonic Knight, astride a dark charger. The pathetic man behind such propaganda was in reality allergic to horses and by all accounts an poor horseman. One of his first actions upon coming to power was to abolish all the cavalry divisions in the German Army – much to the chagrin of his Generals in the Russian Campaign who actually had to do the fighting. Hearing a friend comment about a statue of Fredrick the Great without a horse, Hitler remarked “what difference would a horse make? They all look the same and only spoil the concentration on the figure of the rider”.2 Obviously Hitler had no love of horses that would motivate his next actions in his quest for the Perfect Horse – as always, it came back to another form of selfish ambition.

The Nazis As Horse Thieves

The Germans employed several knowledgeable individuals from different equestrian disciplines to see this project come to fruition. One of the major influences on the project was Gustav Rau; an equine expert and advocate of eugenics who was in charge of all horse breeding in the Third Reich. Another key player was Olympic Gold Medalist and director of the Spanish Riding School of Vienna, Alois Podhajsky. Together they confiscated 600 of the finest horses in Europe. They sought breeds that were intelligent, fiery yet pliable, strong, swift and agile; but all the while they chose candidates based on one common denominator that was in essence trivial, but vital to the obsessive breeding program: they had to appear “white” (or Schimmel) in appearance. This color, officially known in the horse world as grey, was key to look that the Third Reich was trying to achieve.

The breeds that caught the attention of Nazis working on the Ultimate Warhorse project just so happened to be some of the most valuable and ancient breeds in all Europe. The first key breed was the royal Lipizzaner. Named for the Medieval Spanish origin of the breed, this breed was first refined by the Hapsburg royal family of Austria in the 16th century. These horses were steadfast, strong, agile with a good amount of bone to aid their athleticism. They were as rare and precious as any of the priceless masterpieces Germans would steal from the finest art collections in France. While the stallions remained in Vienna, the mares were transported to Hostau in Czechoslovakia, to be the the foundation of a new breed.

“We have to promote inbreeding of the best bloodlines…” wrote Gustav Rau, who clearly did not understand the connection between inbreeding and increase incidence of genetic defects. He claimed he could produce his ‘Equine Master Race’ within 3 years – the damage done to the genetic diversity and overall resilience of the respective breeds would have been devastating if he had accomplished his goal.

A second selection of bloodstock was made by targeting the Polish Arabians. Prior to the 1700’s the Polish people had acquired the mounts of their Middle Eastern and Asian adversaries – even making expeditions into the dessert to import Arabian horses. The Polish Arab embodies tough, endurance qualities paired with a physically beautiful carriage and and fiery temperament. Refined over hundreds of years – and nearly wiped out during the Great War – these equines would become a key component to the breeding program. The disturbing irony to the theft of these Polish horses is the disparity with which the Nazis treated a Nation’s horses in comparison to it’s people. While the horses of Poland were transported in the finest accommodations, human beings were crammed into train cars with far less compassion.

In addition to these two breeds, French Thoroughbreds were seized. While Thoroughbreds were known for their sheer speed, they tended to most commonly appear in darker coat patterns like chestnut, bay and black. The Nazis selected those few thoroughbreds carrying a recessive grey or white coat.

The ultimate goal was to breed out “impurities” and variations within the breed, so that each horse appeared to be popped out of a perfect mold. The German’s understanding of inherited traits was fairly primitive, as they believed there was a pureness or set of uncorrupted traits inherited by “pure blooded” animals. “We have to promote inbreeding of the best bloodlines to get identical germ plasm to prevent corruption and to preserve it,” wrote Rau, clearly oblivious to the dangers of inbreeding, simply thinking that doubling up of purebred genes would only improve quality. The truth was that inbreeding would increase the occurrence of congenital and genetic defects as well as other deleterious recessive traits.

The Approach of the Allies Meant Death for The World’s Finest Horses

When the fall of the Third Reich was imminent, Gustav Rau recognized the danger his breeding facility was in, as the Russians sped towards Hostau from the east. The relationship that Russians had with horses had been strongly impacted by the peasant resistance to collectivism and the government in the 1930’s: this resistance was manifesting in the killing and later consuming of their work horses. This was a method of passive resistance that fueled the 1933 famine that stemmed from government imposed grain quotas being rejected by an unwavering peasant work force.3 This tension between the people and government reinvented the attitude towards horses as separate from other forms of livestock. Horses were no different than cattle in the eyes of the Soviets; they ate horse meat out of preference, not necessity.

The repercussions of this attitude were evinced in the treatment of notable horses by Soviet troops. When the famous Thoroughbred, Alchimist, who combined three of the greatest bloodlines in the Main Granditz Studs was caught by Russian troops, they quickly grew frustrated with the horse’s apprehension about being loading into their truck and shot him on the spot. A similar incident occurred at the Royal Hungarian Riding School in Budapest (which also housed prized Lipizzaner horses). Eighteen of the precious stallions were shot to serve as rations for the Russians – the remaining four were used to pull ammunition wagons. The grooms and riders who had tried to shield their horses from the Soviets were killed without hesitation.

Rau fully understood that if the Soviets were to capture his breeding facility, it would most likely be the end of some of the most treasured horse breeds in modern history. He knew that his only hope would be if the Americans coming from the West reached him first – something of a physically impossibility when considering how the two armies were converging. Rudolph Lessing, the veterinarian in charge of the care of the horses at Hostau made a decision that could be seen as treachery against the Third Reich; he rode to the American lines, begging that they might negotiate their surrender and the rescue of the priceless animals.

General Patton, Avid Equestrian, Answers the Call for Help

Luckily for Lessing, the man in charge of the United States army was himself a horse-lover – George Patton had been an Olympic equestrian in 1912. Patton called on Virginia’s ace rider Colonel Hank Reed of the U.S. Cavalry to make the daring move 50 miles beyond their lines to rescue the horses. He added that if the mission were to go awry, he would not take public responsibility for giving the order – he left the final choice in the matter with Reed.

Reed was eager to take on the daring mission, explaining how “after years of fighting, we were so tired of death and destruction; we wanted to do something beautiful,”4 and he sent American Captain Tom Stewart to return to the breeding facility with Lessing, to assess the situation and negotiate the surrender.

“Get Them. Make it fast.”

– Gen. George Patton’s order for the rescue of the hostau horses

The veterinarian hid Captain Stewart in his room while he went to the convince the German commanders at Hostau to surrender to the Americans. He begged them to think of the welfare of the animals in their care.

“The Americans wish to assist you in evacuating the horses safely back across the border to Bavaria,”5 read the letter Stewart wrote to the hold-outs at the facility; this letter together with the pleas of Lessing convinced them to accept defeat (which by now they knew was inevitable) and seek the means to salvage the horses they had cared for over the last 4 years. By this time, Gustav Rau had long since departed for his own safety, and Hitler had committed suicide in his bunker; they knew the end of the war was near.

The Germans took a white bed sheet and ran it up the flag pole; within hours the American troops took over the farm and began hastily preparing for an evacuation. The scene that greeted Stewart when he arrived presented him with endless obstacles. Many mares were in advanced staged of pregnancy and would have to have their foals first, but even then would need to be moved using large trucks. Stallions would need to be herded well away from mares to prevent scattering the highly-strung horses into the surrounding war-torn countryside. There was no precedent for this daring move – while art and artifacts were protected, horses just a prized and precious had no such official protection.

Reed enlisted the help of 26 Cossacks to work as outriders – the Cossacks and their ponies were stationed at the breeding facility as allies of the Germans. Hitler valued the abilities of the Cossacks, and he proclaimed them an “Aryan People”. Cossacks would fight both for and against Germany in WWII.

Just as the Americans were preparing to leave, they encountered Waffen SS troops who surrounded Hostau, determined to fight to the bitter end. Colonel Reed, fought it out with them, finally taking control of the situation. American tanks and small artillery pieces were positioned to receive the Red Army as the bore down on the town and the horse breeding farm When the Soviets arrived, Reed had to lie to the Soviet troops, insisting they were behind American lines and had no jurisdiction in the town. “If you go forward,” Reed warned, “Just remember that our guns are loaded.” This delayed the Russians who needed to check in with their high command, while Reed rushed to the farm and began Operation Cowboy.

Operation Cowboy Successes

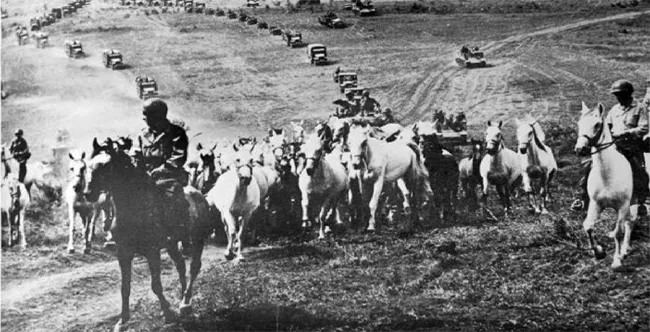

The evacuation began on April 28th, 1945. Thirty stolen German trucks carted mares and their foals in the front. The main herd of horses were separated into three large groups, herded by Cossack outriders on their ponies and Americans on Thoroughbreds. They were moved for 20 minute intervals and stopped to prevent snarl-up’s and traffic jams. There were roughly 600 horses in total. In the rear, were more trucks filled with supplies. Many of the Germans and their families came along as well, preferring to surrender to the Americans than the Soviets. The horses (who were refined breeds, not necessarily hearty or sturdy) found traveling on the road, forests and ravines difficult after living in grassy pastures and they require constant veterinary care to offset lameness. After one final show-down with Czech partisans holding a bridge, the Americans brought the horses safely to American held territory.

Patton announced that the horses were under the protection of the American Army, and was determined to offer the best chance of survival to each of the rare breeds Hitler had stolen. He vetoed the suggestion to move the Lipizzaner horses to the U.S., but instead had 244 mares herded back to Austria, where Alois Podhajsky was protecting the Lipizzaner stallions at the Spanish Riding School of Vienna. This ensured that the bloodline of the Royal Lipizzaners was safe – and the breed continues to this day. While many other horses were repatriated, the determination was made that remaining equines should be moved to American soil, as the threat of their being used as food for bands of refugees loomed. Among those horses transported to the United States for safety was Polish stallion Witez II, who sired 223 foals, 16 of which were were national show champions.

- DiNardo, R. L., and Austin Bay. “Horse-Drawn Transport in the German Army.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 1988, pp. 129–143, doi:10.1177/002200948802300108.

- Hanfstaengl, Ernst. Hitler the Memoir of the Nazi Insider Who Turned against the Fuhrer. Arcade Publishing, 2011.

- Demers, Alanna, et al. “They Kill Horses, Don’t They? Peasant Resistance and the Decline of the Horse Population in Soviet Russia.”

- Letts, Elizabeth. The Perfect Horse: The Daring Mission to Rescue Priceless Stallions from the Nazis. ReadHowYouWant, 2017.

- Letts, Elizabeth. The Perfect Horse: The Daring Mission to Rescue Priceless Stallions from the Nazis. ReadHowYouWant, 2017.