In a letter dated June 28, 1879 former Confederate President Jefferson Davis accused the government of the United States of an atrocity during the Civil War that seems beyond comprehension. The letter was written to a Mister Horace Hayden who formerly served with the 1st Virginia and 1st Missouri Cavalry. Davis vehemently argued that the north was guilty of a “treachery” that was “an atrocity beneath knighthood”. Davis’s letter would be published in Volume VII of the magazine Confederate Veteran as would Hayden’s feelings on the subject. Both individuals were talking about the North’s use of Samuel Gardiner’s 1862 invention, the “Gardiner Shell”. But exactly what was this evil instrument of war? 1

Samuel Gardiner, of New York city, would approach the United States government in early of 1862 with what he considered to be a new type of bullet for use by the military. His “Improvement in the Construction of Hollow Projectiles” was not a new concept. In 1824 a similar bullet was in production by the British for use in their Baker Rifle. Also, the British East India Scinde Irregular Horse Regiment from 1840 to1850 utilized another type of this round in rifles built by British gunsmiths Swinburn and Son. This British .52 caliber hollow bullet was fitted with a fulminate of mercury fuse and filled with black powder making the bullet explode once the fuse reached the powder charge. What Samuel Gardiner was proposing was the use of his version of an exploding bullet by the United States military.2

Gardiner’s version of the bullet was based on Frenchman Claude Etienne Minié’s “minié ball”. Minié had improved the conical shaped lead projectile based on the design of Henri-Gustave Delvigne which incorporated “expansion rings” around the bullet’s base. These rings, once the rifle was fired, expanded to catch the grooves in the rifles barrel. Minié added a concaved hollow to the bullet which not only aided in the bullet’s expansion but improved the minié’s accuracy. Gardiner’s design incorporated a hollow copper bowl or “cup” inserted inside the molded bullet in which fulminate of mercury or slow burning black powder was placed. A fuse would then be inserted into a small port of the cup and when the rifle was fired, the fuse would ignite. The charge in the bullet would explode when the burning fuse reached the internal explosive causing the bullet to fragment. According to ballistic information, a typical .58 caliber bullet traveled at around 1100 feet per second. Because Gardiner’s exploding bullet weighed slightly more than the standard minié round, and the fact that the fuse was set to detonate within 1.25 seconds, the shooter had to be within 450 yards for the round to be effective. It is easy to see where this type of bullet would evoke criticism and hatred from an enemy if used against personnel. 3

“Ripley would refuse to even think about purchasing such a deplorable devise. He rationalized that using this type of bullet on another soldier was inhuman. What Gardiner had not made clear to Ripley was that the bullets were intended to be used against artillery caissons and ammunition chests.”

West Point would test Gardiner’s ammunition in May of 1862 and the results were well received. Gardiner would then approach General James Ripley the North’s Chief of Ordinance. Ripley would refuse to even think about purchasing such a deplorable devise. He rationalized that using this type of bullet on another soldier was inhuman. What Gardiner had not made clear to Ripley was that the bullets were intended to be used against artillery caissons and ammunition chests. In September of 1862 the northern Army of the Potomac’s XI Corps, hearing of Gardiner’s invention, circumvented Ripley and went straight to Secretary of War Simon Cameron in order to obtain the bullets. Cameron initially ordered 10,000 rounds but only 200 would be issued as a trial run. After seeing the effectiveness of the round, the leaders of the XI Corps would request another 20,000 in October of 1862. The corps would only receive the remaining 9800. However, the War Department would order an additional 110,000 rounds in .54, .58 and .68 calibers at the price of $35.00 per 1000. Gardiner would eventually patent his bullet on November 23, 1863 (Patent #40468). 4

The 2nd New Hampshire Infantry would be one of the initial units to receive the Gardiner round. Requesting 35,000 rounds in June of 1863, the unit would obtain 24,000 to be used during the Gettysburg campaign. 10,060 of the bullets would be left in Virginia and 13,940 carried north. The 2nd New Hampshire would utilize the bullets at South Mountain, Maryland and at Gettysburg on the second day of the battle in the infamous Peach Orchard. However, several of the Granite Staters would be on the receiving end of Gardiner’s invention in Pennsylvania. 5 During the fight for the Peach Orchard one private in the 2nd New Hampshire would be near an artillery burst and the resulting sparks entered his open cartridge box igniting the paper wrapped rounds causing them to explode. The result was some of the rounds entered his body and caused him to “jerk and quiver” for over 30 seconds as each exploded. Another case involved a fellow member of the unit having a similar occurrence. He was more fortunate and was able to tear his cartridge box off in time only receiving a nasty burn. Due to incidents such as these the U.S. War Department stopped the issuance of the Gardiner round for the remainder of the war. 6

A Confederate report indicated that the Union Army used exploding bullets during the Union’s Peninsula Campaign in the spring of 1862. In a January 1899 issue of Confederate Veteran magazine an article penned by Judge Henry H. Cook reported that he personally heard “at least twenty bullets explode” over the heads of his Confederate comrades. There is one problem with Cook’s story. Gardiner had only introduced his exploding round that same month and the Union army did not purchase any until September of that year. There is a possible explanation for Cook’s claim. 7

Philadelphian Elijah Williams had invented what came to be known as the “Williams Cleaning” bullet. He would receive a patent on December 9, 1862 for the invention. His conical shaped bullet consisted of a flat zinc washer base attached to the lead head by a wooden or alloy post. The zinc washer, upon the bullet being fired, was intended to clean any black powder build up inside the firearms barrel. For every ten-round pack of ammunition issued to a soldier, one of Williams’s cleaner bullets was inserted. Several reports by Confederates attribute the Williams round as being an exploding bullet due to the fact that the bullet would oftentimes come apart in mid-air. Williams would eventually develop three versions of his cleaning bullet during the war. However, the Union army would discontinue their use in September of 1864 due to the fact it was found that the zinc washer damaged the rifling in a weapons barrel. 8

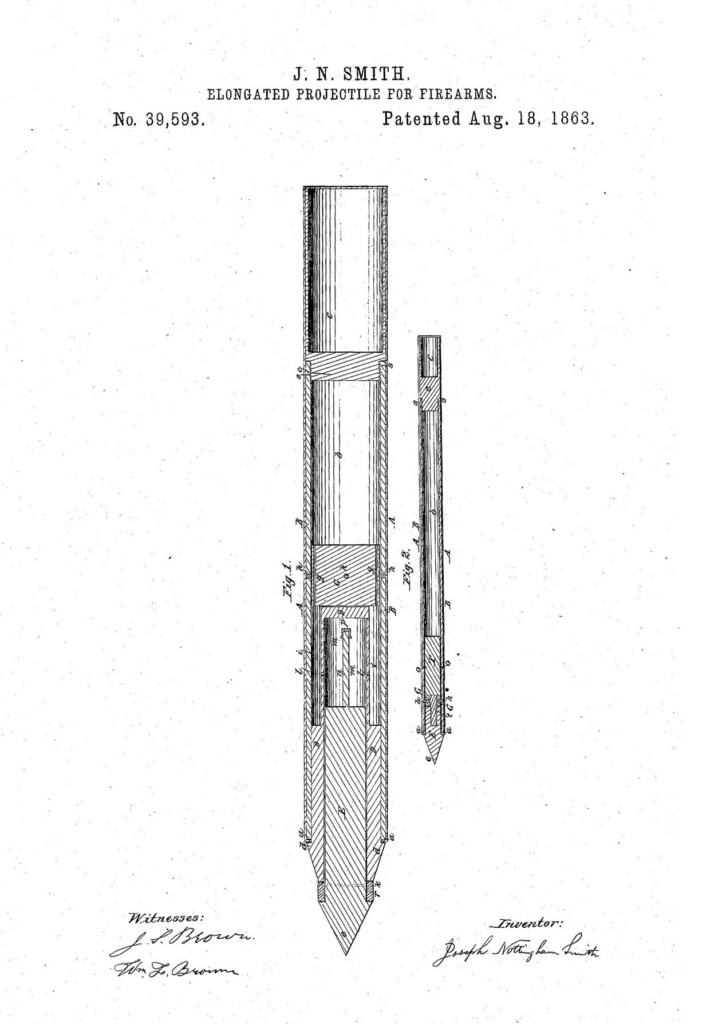

There are few if any known accounts written by Confederate soldiers of anyone from their side being on the receiving end of an exploding round. One in particular was a letter cited by Horace Hayden, in his Article for the Southern Historic Society Papers. The letter was from an individual F.J.C. published in the Scientific America magazine (Volume VIII pages 22-28) dated September 6, 1862. F.J.C. stated he found an exploding round after the 1862 Seven Days Battles in Virginia near Fortress Monroe. The bullet was “Conical in shape about one inch long, made of lead and consists of two parts – vis: a solid head piece and a cylindrical chamber, which are united by a screw. From the point of the bullet projects a little rod, which passes through a small hole in the head piece into the chamber below, where it was connected to a percussion cap. The chamber contains about a tablespoon of powder.” Hayden would misidentify the round as one allegedly invented by a Joseph Smith. Smith’s invention was actually several feet long and looked something like a modern-day model rocket without the fins. 9

So what was this strange “explosive” bullet?

Given the description, it appears that the bullet was one manufactured by French born Louis Francois Devisme. Devisme was a maker of ornate and unique firearms and developed explosive rounds for use on large game such as bison, elk and bear. Jefferson Davis, as well as Confederate Cavalier J.E.B. Stuart, and Generals Robert E. Lee and John Bell Hood all owned Devisme weapons. In fact, after Davis was captured while trying to flee after the fall of the Confederate capitol of Richmond, a Devisme rifle and explosive ammunition were found in his baggage. 10

There is indisputable evidence that the north utilized exploding ammunition. Further research shows that Davis and his Chief of Ordinance, General Josiah Gorgas, denied that the Confederate government ever authorized the use of explosive ammunition by southern soldiers. They did admit that captured ammunition may have been used by their army. Their claims are further supported by the U.S. Adjutant General in 1879 who stated that there was no captured Confederate documentation from the war in which exploding bullets were used by the South. However, there is abundant evidence to prove them wrong. 11

A young soldier from an Iowa regiment was wounded in the leg during William Tecumseh Sherman’s march through Georgia somewhere near New Hope Church in 1864. Upon receiving the wound, he was able to limp to a nearby regimental hospital and after arriving sat down to await his turn. Suddenly his leg exploded causing the wound to become larger. Another account is that of Theodore Lyman, Aide to Union General George Meade. Lyman claimed that during fighting in Virginia he personally observed bullets that “When they strike they explode like a fire cracker, and make a bad wound.” Still a third individual from the 72nd Illinois found .54 caliber bullets that fit the Harpers Ferry musket. These rounds when fired “scattered fragments in every direction”. Other reports show Confederate use at the battles of Snickers Gap in 1864, Corinth Mississippi and Port Hudson, Louisiana. Captain William Farley, a member of J.E.B. Stuart’s staff, openly admitted to using exploding bullets against Union personnel at the battle of Gaines Mills. Farley initially wanted to utilize his own personal weapon, an English made double barrel rifle, upon Union artillery caissons. However, he decided to try them on northern troops. His first victim, a Union officer, did not die outright. Farley was able to approach his victim afterwards and saw that he was still alive. Farley felt no remorse and according to him he utilized around 80 rounds of the devastating ammunition that day. Even General Ulysses S. Grant, in his memoirs, stated that during the siege of Vicksburg the rebels used exploding bullets against his troops. Grant’s claim is further proven by a soldier from Perry, Illinois who found an ammunition crate after the fall of Vicksburg marked “Exploding Ball-1000 rounds, 58 caliber… manufactured at Charleston, SC., C.S.A.”! 12

Did the south actually manufacture exploding bullets to be used by their troops without the Confederate government’s knowledge? The answer is yes. Lt. Beverly McKinnon, of the southern Navy, reportedly had the Richmond Arsenal manufacture 100,000 explosive rounds in .54 and .69 caliber for use on navy ships. After the fall of New Orleans in April of 1862, some were captured by northern troops and 39,000 were found stored at the Confederate Naval Lab in Atlanta after it’s capitulation. It is quite possible that besides being made for the Confederate navy some found their way into the southern infantry cartridge boxes and as stated earlier, captured and personal ammunition were used by southern troops against their northern counterparts. 13

“Did the south actually manufacture exploding bullets to be used by their troops without the Confederate government’s knowledge? The answer is yes.”

It is apparent that the use of exploding bullets against individual soldiers was rampant during the Civil War. It’s intended purpose against artillery ammunition chests and caissons can be understood. However, the barbaric and indiscriminate use against a human being is hard to comprehend. In 1886, a call was made by the Russian government to outlaw exploding bullets during war time. Considered to be an uncivilized method of conducting war against an adversary, the United States Army and War Department concurred with the Russian proposal. Their rationale was that the killing of an individual soldier outright was less invasive on the use of personnel than a wounded soldier. The dead could be dealt with at a later time, however, a wounded soldier required at least two others to carry him from the field. Despite this, even if the use of exploding bullets would have been continued against artillery ammunition containers, the resulting blast would still have incurred human casualties. Therefore, this argument becomes mute. Still the development of better ways to kill during warfare continues to this day and will do so into the future as long as mankind wars against itself. 14

- Cook, Henry C., Confederate Veteran, Volume VII, pages 157-157.

- Austerman, Wayne, “Abhorrent to Civilization”, Civil War Times Illustrated, Volume XXIV Number5, pages 28 and 38; www.googlepatentsearch.com: U.S. Patent Office, patent #40468 dated November 23, 1862.

- Ibid.

- J.M. Shofeild, U.S. Secretary of War letter dated august 19, 1868 to the Southern Historical Society Paper, Volume VII, page 23; Austerman, page 38.

- Austerman, page 38.

- Ibid.

- Cook, Henry H., page 27.

- Hess, Earl J., The Rifled Musket in Civil War Combat, University of Kansas Press, Lawrence Kansas, page 77.

- Haden, Horace E., Exploding Bullets, Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume VIII, page 27.

- www.nps.gov/spar, Springfield Armory Historical Site, National Park Service, Springfield MA; Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, United States Government Printing Office, Series 1, Volume XLVII, part 3 pages 652-654.

- Confederate Veteran, Volume VII, page 157.

- Burlington Weekly Hawkeye, Burlington Iowa, August 27, 1864, page 6; Lyman, Theodore, Meade’s Headquarters, 1863-1865, edited by George Agassiz, 1922, page 81; The National Tribune, August 26, 1886, page 3, October 26, 1886, page 4, November 4, 1886, page 3; Austerman, page 39; Grant, Ulysses S. The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: The Complete Annotated Edition, Edited by John F. Marszalek, 2017 page 372.

- Scharf, J. Thomas, History of the Confederate States Navy, page 49; Hess, page 78; Austerman, page 40.

- Confederate Veteran, Volume VII, page 158.

NiobeVerified

A very informative read!

It’s unfortunate that the Gardiner’s bullets were turned on soldiers. Usually I think of the minie bullets as being highly damaging ammo, but I suppose the bullets were larger with a lower velocity than modern bullets (smaller size and higher velocity). The result was men with grievous wounds, but still alive to be taken to field hospitals. It’s hard to know whether it’s better to live with some of those injuries or not.

These exploding bullets sound like they would have been terrifying to encounter.

brianstammVerified

Thanks. It is subjects like this that make history more interesting.