Textiles have played a key part of the history of the American colonies, and were of pivotal importance not only from a necessity standpoint, but as leverage for freedom from Britain as well. Who would have thought that a few yards of cloth could say so much about a person’s social status, political leanings and religious sympathies? This article will outline the unique qualities that made certain fabrics synonymous with rebellion or loyalty, as well as how resourceful colonists made fabrics from a selection of fibers.

Where did colonists get the fabrics for clothing?

The primary fabric sources for American tailors and dressmakers to choose from was imported cloth from England and abroad – or homespun (domestic) cloth.

Imported Fabrics

The cheapest source for fabrics of both fine and rustic quality was buying imported products. British imports dominated the market up until just prior to the Revolution. But just as the British wanted American consumers to buy from them, they didn’t want to jeopardize their trade by exporting American-made cloth back to England. It wasn’t a bad deal for the colonists in some ways: the British textile industry employed thousands while utilizing the latest and fastest looms for producing cloth, resulting in handsomely low prices. Each year, Americans imported hundreds of thousands (and some years, millions) of yards of fabric from England. This would have been a wide range of varieties, from silks, velvets and muslins to practical cotton and linen.

Toss the Tea – But Keep the Textiles.

British textiles were the single largest import to the American colonies. In the past, historians believed American households were mostly self-sufficient, including manufacture of their own fabric based on the fact that they never slaughtered sheep for food and most planted patches of flax annually. Research into the sheer amounts of imported textiles contrasted with the scant production from domestic mills paints a very different picture of what the average American would have worn. Textiles kept colonists dependent on English trade.

Records of merchants who supplied cloth (called “stuff” in the 18th century) to colonists show a great quantity of osnaberg (a rather coarse linen reserved for the clothing of slaves) as well as sheeting and holland passing though their shops. Thomas Jett, a merchant from Leedstown, Virginia wrote to his suppliers in London: “I am in great want of German osnaburg, it’s an article that always sells well with us, therefore should be glad to have a pack or two by every opportunity.” These accounts imply that even the roughest sort of cloth was being imported as opposed to manufactured in the colonies.

Homespun Fabrics

Homespun was fabric made from a range of fibers produced, spun and woven into fabric by colonists. It generally was a rougher material than what was imported from the Orient or England, since the technology for weaving and finishing fine fabrics was closely guarded. It was only when notable weavers from England immigrated that they brought their tech with them to the colonies. Samuel Slater, a weaver from England, set up the very first factory in the United States in 1790 – it was a water-powered cotton mill, using the foremost in cutting edge technologies for spinning and weaving available for the era.

“… What if homespun they say, is not quite so gay

As brocades, yet be not in a passion,

For when once it is known, this is much worn in town,

One and all will cry out ‘tis the fashion!”

– “Address to the Ladies,” 1786

A key factor that drove the manufacture of homespun was the lack of currency in the American colonies. England did not strike enough coinage for the colonies and they also prohibited colonists from minting their own; the result was a burgeoning barter system. Turning flax and wool into thread and yarn – which in turn could be made into cloth – was a lot like printing their own money. In bad weather or off seasons, colonists practiced the skills associated with textile production at home. In many ways, the production of homespun typified the American ideals of the time: they could take resources at hand and use their own industriousness to produce items they needed in their off time as a means of furthering their own self-sufficiency.

In years leading up to the Revolution (and again during the embargoes of the early 1800’s), wearing suits made from homespun became a symbol of patriotism and support of breaking ties with England. Homespun became a revolutionary’s fabric of choice because it bypassed British taxes on imported cloth. At an event in 1769 Virginia, dubbed “the Homespun Ball”, members of the House of Burgesses dressed entirely in homespun as a demonstration of their antipathy towards British powers that had dismissed their governing body six months prior.

“[I]t is with the greatest pleasure we inform our readers that the same patriotic spirit which gave rise to the association of the Gentlemen on a late event, was most agreeably manifest in the dress of the Ladies on this occasion, who, to the number of near one hundred, appeared in homespun gowns; a lively and striking instance of their acquiescence and concurrence in whatever may be the true and essential interest of their country. It were to be [wished] that all assemblies of American Ladies would exhibit a like example of public virtue and private economy, so amiably united.“

— The Virginia Gazette, December 14th 1769

The process of making homespun was labor intensive and when factoring in the hours involved, the price of a homespun suit was considerable and the ability to supply such articles in bulk was low. In 1770, Lancaster Pennsylvania had set up 50 looms and employed 7,000 spinners, producing 30,000 yards of cloth a year according to the Derby Mercury. Even with such industrious manufacture of cloth happening on American soil, when war broke out the demand for producing tents, uniformed and all sorts of necessary gear quickly depleted fabric supplies. Homespun production could not keep up. It was the French who came to the rescue militarily and “materially” as they imported much needed fabrics until peace with England caused British imports to resume.

What types of fibers did colonists use to make homespun?

Flax

Flax is a natural plant fiber harvested from the stems of the Linum usitatissimum plant. This crop was similar to tobacco, in that cultivation required rich, sweetened soil and then in turn the plants would deplete the ground they grew in. Preparing it for use took many steps:

- Rippling: When the leaves on flax plants turned yellow, the flax was harvested. The roots were cut off. The seeds were removed using a rake in a process called rippling. If there were no time constraints, farmers would store flax in barns for processing the following year.

- Retting: In order to break down the unwanted external plant material, called boon, and reveal the fibers inside the stems, the flax was either left out where the elements would break them down, or placed in a pond (though the smell was unpleasant) or anchored in a running stream (ideal).

- Drying: Once the plant material easily pulled away from the inner fiber, the flax was laid out in the sun to dry. It would be turned to ensure both sides were thoroughly dried.

- Scutching: Dried flax would be put through a blunt chopping tool called a flax break. This broke off the stemmy material still attached to the flax fibers.

- Hackling: The flax fibers are passed through a series of metal combs, to separate the individual fibers. The result was long strands of glossy fiber, ready for spinning on a Saxony wheel.

Cotton:

Cotton was another fiber crop that demanded well cultivated ground with rich soil. Another vital requirement was temperature, as it was necessary to have days that averaged around 77 degrees and where there were 200 days between frosts. Pennsylvania could not accommodate these conditions, but colonies farther south could. In the 18th century, cotton was usually only a “patch crop” of 10 acres or less until the early 1800’s, when Eli Whitney’s cotton gin processed the crop efficiently enough that cotton could be planted extensively. Up until this point all of the skilled labor for manufacturing fine cotton fabrics was found in India and exported to Britain and the colonies. Cotton was spun on a walking wheel – most of the small crops of cotton grown by southern colonies were processed for their own use or domestic bartering. Spinning cotton was notoriously difficult compared to other fibers due to the short staple length of the fibers and the lack of barbs on the epicuticle of the fiber that keep the spun fibers held together.

Wool:

Sheep in the American colonies were rarely used for their meat, but were kept to produce wool. Britain prohibited the export of sheep to the colonies as well as the import of colonial wool products back to England as a means of protecting their own wool industry, but sheep were nonetheless smuggled in and provided wool for weaving, knitting and felting.

Sheep husbandry was a difficult task in the colonies, due to the prevalence of predators looking for an easy meal. For this reason, sheep were often kept on islands to protect them. In the case of the Hog Island sheep breed, colonists allowed the animals to live independently for years – their small size became an adaptation to life in the wild. Colonists would round sheep up once a year, taking some by boat to market and allowing the core herd to freely roam and proliferate on the island. In the 1930’s, hurricanes forced the few inhabitants of Hog Island to leave – though they took the bulk of the herd with them, some remained behind, survived and today represent almost exactly what sheep would have looked like in the 1700’s.

Other popular breeds in the colonies were the Ryeland, Southdown, Dorset and large longwool breeds. To process wool, the sheep were sheared and the wool was picked and washed clean, then carded to line up the fibers allowing spinners to easily work it into a twist with their spinning wheels.

Knitting was a method of easily producing warm garments from a colonist’s fiber flock. Stockings, caps, gloves, mittens and men’s waistcoats (casual outerwear for in the home, sometimes called “Florentine jackets”) were all popular items that could be knitted at home during the 18th century. Some of these items were knitted larger than needed and shrunk to fit, creating a dense, insulative knit.

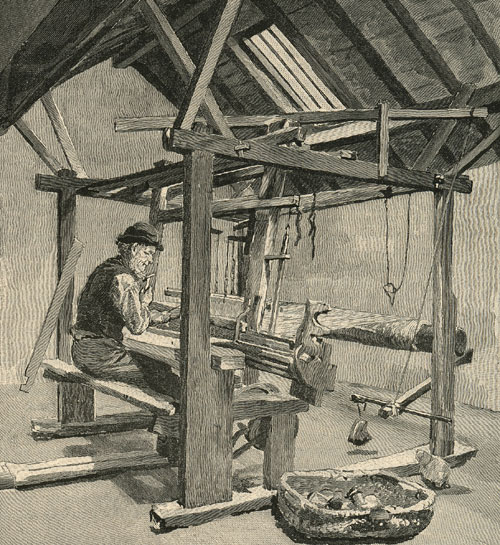

The Role of the Weaver

In England, the role of the weaver was exclusively male from the early 15th century and onward – laws were in place restricting women from weaving until 1825. This concept was transported to the colonies, where weaving would be predominantly done by men who had been apprenticed in the trade as boys. Owning a loom was cost restrictive to most, so colonists would bring yarn to an established weaver, who would turn it into cloth.

Spinning was a job that was dominated by women. Anywhere from 5 to 15 spinners would work to supply enough yarn for a weaver to make 12′ of broadcloth. The English custom held that if a weaver died, his widow was allowed to take up the trade until she remarried.

How much clothing would someone in the 18th century have owned?

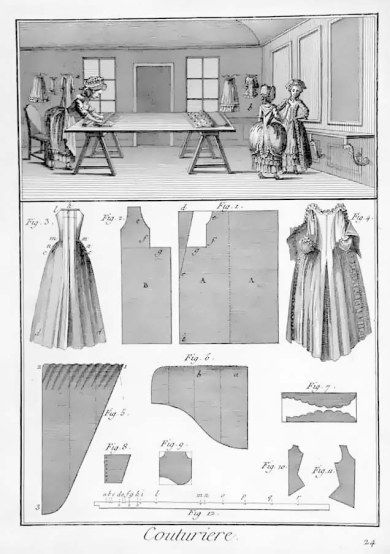

Procuring clothing was a very expensive undertaking in the centuries leading up to the 1700’s. This is due to the labor intense process of producing cloth and manufacturing garments – virtually nothing was available to be bought ready-made. Gregory King’s ‘Table of Apparel’ of 1688 provides probate accounts from the late 1600’s record detailing the expenses of impoverished persons living in England – the average cost of clothing was only slightly less than what was spent on housing, which was the largest recorded expense. For the poor, they may only own the clothing they wore. As a comparison, Martha Jefferson (Thomas Jefferson’s wife), made an inventory of her clothing that numbered her total wardrobe at 16 gowns (with two additional that were being ‘made up’), 9 petticoats, 18 aprons and 20 shifts. While Martha Jefferson would represent a more opulent selection of clothing, for someone of the “middling type” the total number of garments would have been 3 to 4.

Clothes on Credit

Queen Marie Antoinette had an annual budget of 120,000 livre (over $3 million in today’s money) to spend on apparel – she notoriously would spend over her budget, sometimes up to 100%.

The average American colonist could find themselves in a very similar situation, as they were often acquiring clothing on credit and would be expected to pay when crops were harvested. In this way, a colonist could spend beyond their budget on clothing and find themselves in debt if crops failed or market values for their goods plummeted.

How fashionable were American colonists during the 18th century?

By the mid-1700’s, Philadelphia had become a bustling metropolis – the river was busy with ships bringing the finest goods and latest fashions from across the globe. In terms of fashion, the city was comparable to the trendiest corners of London and France. Macaroni, young men who lavishly dressed themselves for an average day in clothing usually reserved for court based on it’s sheer fineness and extravagance, walked the streets of Philadelphia.

Yankee Doodle

In the British ditty Yankee Doodle, the lyrics mock the Americans for their uncouth ways. The line “Stuck a feather in his cap / and called it Macaroni…” was intended to illustrate how out of touch they are with the trends of refined society. The song was written at a time when the Macaroni style was in vogue, but the trend itself was so short-lived that within ten years the Macaroni fell from grace and became a made-to-order target for all sorts of ridicule, including cartoons like the one on the left, where a hairdresser follows his customer to support the massive wad of hair on the back of his wig.

During the American Revolution, styles would become simplified and martial as high fashion would be seen as synonymous with the excesses and tyranny of the Old World.

The city wasn’t just fashionable, it was saturated with the latest and finest imports, as merchants often docked with boats full of finery to simply auction it off on shore to the highest bidder. In this way, Philadelphians acquired merchandise without the additional mark-up’s of the shops. Cunning shop keepers would procure the latest styles from Europe and using domestic supplies, they would recreate them for a cut rate price and with New World flair. The city was glutted on affordable fashions.

The distance to Philadelphia from outlying counties like Berks was only a day and a half’s ride. It was possible – especially for those where money was no object – to send an order to the city for the latest and greatest fashion and receive it within three or four day’s time. Life in the smaller towns surrounding Philadelphia was not so far off from having their own sort of Amazon.com, where just about anything could be purchased and received in rapid succession.

Gallery

Additional reading sources:

Textile Consumption and Availability: A View from an 18th Century Merchant’s Records – Leslie Anne Bellais – College of William & Mary – Arts & Sciences: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5076&context=etd

The Market for Manufactures in the Thirteen Continental Colonies, 1698-1776 – S. D. Smith – The Economic History Review: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2599568

REAL COLONIAL WOMEN DON’T WEAVE CLOTH – Kathy King – Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society

History Quarterly Digital Archives: https://tehistory.org/hqda/html/v43/v43n2p062.html

Cotton in World History: India, Britain and America – Chris Brooks – University of California Santa Cruz:

https://humwp.ucsc.edu/cwh/brooks/cotton/India,_Britain_and_America.html

Made in American – Neal T. Hurst – Trend & Tradition Magazine: https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/trend-tradition-magazine/spring-2018/made-american/

A Brief History of the Sheep Industry in the United States – L. G. Connor – Agricultural History Society: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/44216164.pdf