1. The Olmecs domesticated the cacao plant 3000-4000 years ago – the Aztecs made it a dietary staple.

The earliest known Mesoamerican civilization in history was that of the Olmecs. Though they had a major cultural influence on subsequent eras, no recorded history remains and the Olmecs mysteriously vanished; many theorize because of a plague. In the surviving artifacts found at burial sites, researchers identified specially made chocolate drinking vessels, containing traces of theobromine, the bitter tasting alkaloid found in cacao.

Unlike other cultures, the Olmecs prepared their chocolate with both the bean and pulp. The fresh pulp had a acidic fruit flavor, much like a mango or lychee. The complexity of flavors associated with chocolate comes from the fermentation process, where the beans are left to oxidize and sweat away their juices.

“Fruit of all the kinds that the country produced were laid before him; he ate very little, but from time to time a liquor prepared from cocoa, and of an aphrodisiac nature, as we were told, was presented to him in golden cups… I observed a number of jars, above fifty, brought in, filled with foaming chocolate of which he took some.”

– Bernal Diaz del Castillo, Spanish Conquistador who served under Cortez

The Olmec people consumed their revered chocolate on ritual occasions – but the Aztecs turned chocolate into an everyday necessity. Aztecs drank their chocolate both hot and cold, often pouring the drink over and over to create a frothy head. King Montezuma may have drank 50 cups of chocolate – or as the Aztecs called it, Xocolatl – a day.

2. Before the 19th C, Chocolate was only consumed as a drink

Most modern people think of chocolate and picture the sugary, easily melted confection that comes in bar or morsel forms, but this style of consumption has only been around for the last two-hundred years, making it a very recent plot twist in the history of chocolate. Prior to this, the only way to prepare chocolate was by grinding fermented cocoa beans and mixing with water – often hot water, to emulsify natural oils – to create a beverage.

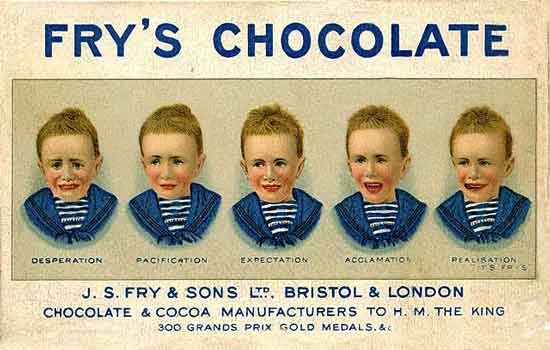

For 90% of Chocolate’s History, it was consumed as a liquid. It wasn’t until 1847 that chocolate was available in the form of a food. British chocolate company J.S. Fry & Sons created the first chocolate bar from cocoa butter, cocoa powder and sugar.

The earliest evidence of cacao preparation were found in the burials of the ancient Olmecs, who believed that chocolate was a gift from their gods. They passed the secrets of cacao on to the Mayans, who in turn passed it to the Aztecs.

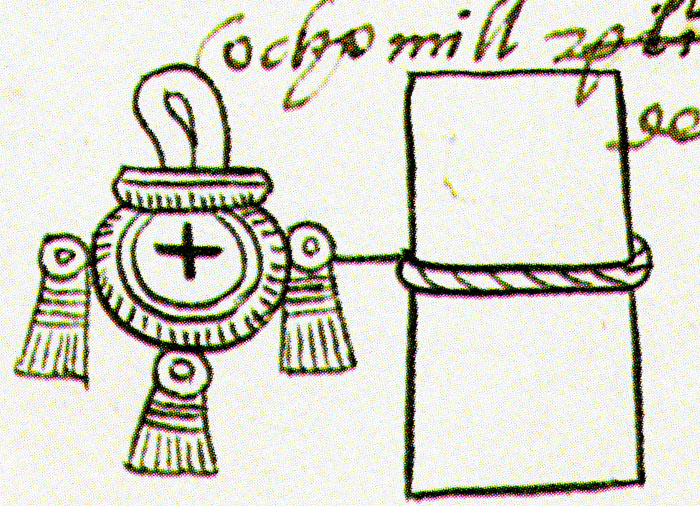

3. Cacao Nibs: Money That Grew On Trees

In ancient Mesoamerican cultures, cacao seeds were used as currency. The precious nature of the cacao seeds made the act of brewing and drinking chocolate on par with swallowing gold – quite a display of disposable wealth! While visiting the New World, Christopher Columbus brought his son, Ferdinand, who made this observation of the Mayan people’s reverence for what he thought were almonds, but were actually cacao beans.

“they had many of those almonds [sic] which in [Mexico] are used for money. They seemed to hold these almonds at great price; for I observed that whenever any of these almonds fell, they all stooped to pick it up as if an eye had fallen.”

Ferdinand Columbus, Son of Christopher Columbus

Special bags, called xiquipilli, were used for carrying large quantities of cacao and as symbolic monetary measurement of 8,000 beans. Beans were used by the Mayans to purchase slaves, precious stones and ceremonial Quetzal feathers – or horded away as liquid assets. The ninth Aztec Emperor, Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (Montezuma II), was renowned for his wealth and power, owning up to one billion cacao beans. In his day, he was known as “The Chocolate King”.

4. Europe Hated Chocolate (At First)

In spite of being revered as a drink from the gods in South America, it took a considerable amount of time for Europeans to get hooked on chocolate.

“It seemed more like a drink for pigs than a drink for humanity … But then, as there was a shortage of wine, so as not to be always drinking water, I did like the others.”

– Girolamo Benzoni, History of the New World from 1541-1556

While regarded as a sacred and noble drink to the Aztecs, the spicy flavorings together with the prejudiced conception that the Aztecs were savages, kept the people of Europe from forming an affinity with the drink. Spanish ships that had cacao as their cargo were unceremoniously burned by British pirates, according to The Cambridge World History of Food. Introduced in 1528, it took until the mid-16th century before the elite in in Europe began to acquire a taste for the beverage – and only after softening the bitterness with their own preferred flavorings. Sugar was a new import for Europeans, who found combining these two New World imports combined with milk resulted in a entirely new obsession. “The drink that came from the Indies” was now a delicacy in the Old World. Other Old World spices, like cinnamon, anise seed and black pepper soon found their way into drinking chocolate.

5. Chocolate Hit Europe Before Coffee or Tea

A question that comes to mind when considering the reaction to the bitterness of imported cacao is ‘wasn’t it akin to the dark biting taste of coffee?’. While the two beverages shared this bitter flavor note, Europeans hadn’t acquired a taste for coffee either, as it would take another 20-50 years before coffee would make it’s way across Europe. Tea would arrive a full century after chocolate, imported by the Dutch.

6. A Drink For Kings & Queens

Much like the Aztecs, who also used cocoa beans as currency, European chocoholics were the nobility, due to the high cost of acquiring the drink. Chocolate was first unveiled in France in 1615, as a sort of novelty to celebrate the marriage of Louis XIII and Anne of Austria. This began a trend for French aristocracy to take to the regal beverage. By the time Marie Antoinette graced the halls of Versailles, she had brought her own chocolate maker with her to prepare her cocoa, trying new experimental combinations, like adding orange flower water and almond essence.

“Place an equal number of bars of chocolate and cups of water in a cafetiere and boil on a low heat for a short while; when you are ready to serve, add one egg yolk for four cups and stir over a low heat without allowing to boil. It is better if prepared a day in advance. Those who drink it every day should leave a small amount as flavouring for those who prepare it the next day. Instead of an egg yolk one can add a beaten egg white after having removed the top layer of froth. Mix in a small amount of chocolate from the cafetiere then add to the cafetiere and finish as with the egg yolk.”

– Louis XV’s Chocolate Recipe

7. Hot Chocolate Had Its Own Serving Ceremony

Marked by William Gamble, London

As the love of drinking chocolate gained momentum in Europe, spreading downward through the middling classes, specially made chocolate pots were produced to fit the finest tastes as well as the most practical applications. These pots were had several identifying attributes. One notable addition to chocolate pots was a hole in the lid, often with a matching milling utensil – or Molinet – to agitate the nibs and emulsify the oily cacao fats into the hot milk or water. These chocolate pots were often outfitted with a wooden side handle to protect the hands from pouring the hot liquid. Sometimes specially made sets of cups and saucers accompanied the pots, to help enhance the presentation and enjoyment.

“On hot chocolate: It flatters you for a while, it warms you for an instant; then all of a sudden, it kindles a mortal fever in you.”

– Marie, Marquise de Sévigné

8. Chocolate Was Prized For Its Medicinal Qualities

Both ancient and modern eras both believed that chocolate had many healing powers. The Aztecs mixed cacao with silk cotton tree bark (Castilla elastica) to produce a concoction for treating infection. When introduced to Europe, chocolate was quickly adopted as a drug. European medicine in the 1550’s was still influenced from classical sources like Hippocrates and Galen, who assigned elements of the four “humors” to each disease and cure. Disease fell into categories like “hot” or “cold”, “wet” or “dry” – cacao was classified as a “cold” element, but was prescribed in either a hot or cold form depending on the ailment it was assigned to treat.

“… the Confection whereof it Treats, together with it selfe, were first admitted into the English Court, where they received the Approbation of the most Noble and Iuditious those dayes afforded. Since which time, it hath beene universally sought for, and thirsted after by people of all Degrees (especially those of the Female sex) either for the Pleasure therein Naturally Residing, to Cure, and divert Diseases; Or else to supply some Defects of Nature, wherein it chalenges a speciall Prerogative above all other Medicines whatsoever.”

– From the 1652 book “Chocolate: Or, an Indian Drinke” by Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma

The fats in historical chocolate helped patients who needed to gain weight do to illness – in the 18th century, many doctos advocated treating smallpox patients with chocolate to prevent the weight loss caused by the disease.

9. The Catholic Church Condemned Sinful Chocolate Indulgence

The religious calendar of the Roman Catholic faith included 100 different days of mandatory fasting. The parameters for fasting allowed parishioners to drink fluids as long as they provided no nourishment. Chocolate quickly became a divisive element, as it was difficult to define whether it was a beverage or food stuff. What fueled this debate were the additions made to certain chocolate recipes – items like egg yolks, blanched almonds and dissolved bread crumbs that thickened and enriched the liquid so that it no longer resembled a mere drink. The debate was finally settled after one-hundred years of scrutiny, when in 1662 Cardinal Francisco Maria Brancaccio declared that: “Beverages do not break the fast, since wine, being as it is so nutritious, does not break it. The same applies to cacao beverage…”

Eating chocolate

“… On the feast of All Souls in nearly all the Indian towns, many offerings are made for the dead. Some offer corn, others blankets, others food, bread, chickens and in place of wine they offer chocolate.’

– Franciscan friar Toribio de Benavente (d.1569)

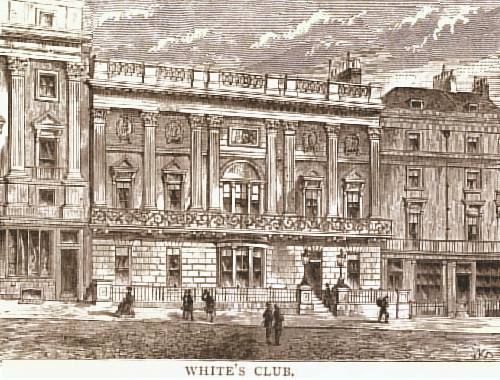

10. 17th Century Chocolate Houses Outclassed Coffee Houses

A long forgotten mainstay of the past are the coffee houses where the public would congregate, share news, make business deals and evolve into the modern stock market. Just as coffee houses were a place for the common man and merchant classes, chocolate houses catered to an entirely different clientele. Buying a drink at a chocolate house was a fairly expensive treat, and was an experience that was savored by mostly upper classes. Fine porcelain with gilded luster details were used to serve the chocolate. With time, many chocolate houses transformed into exclusive clubs.

But by 1663, London had 82 chocolate houses – in England, the houses were not only for the affluent, but for the middling type as well. Unlike coffee houses, chocolate houses were more centers of social change rather than political change.

11. A Dutch Chemist Revolutionized Chocolate

Over centuries, new and revolutionary techniques were devised to make chocolate more and more addicting and available for the masses. Chocolatier Domingo Ghirardelli discovered the Broma process by placing cacao nibs in sacks hanging in a hot room so that the butter separated and dripped to the floor – in this way bitter fats contained in the cocoa butter were isolated from the beans. But Dutch chocolatier Coenraad Johannes van Houten took the refinement of cacao to the next level, devising a process that not only made chocolate taste better, but also allowed it to be accessible to people of all classes. Using a hydraulic press to express the bitter cocoa butter and adding an alkalizing agent, Johannes had essentially made the modern flavor we associate with chocolate today. His method became known as the Dutch Process, and it allowed for cakes of refined cocoa to be pulverized into powder, making for a shelf-stable, palatable ingredient ready to be mixed into cakes, beverages and bars.

12. It Took Until the 19th Century for Chocolate to Take An Iconic Form

It wasn’t until 1847 that an inventor named Joseph Fry combined cocoa powder, sugar and cocoa butter into a paste that could be pressed into molds. The first chocolate bar was born. Subsequent innovations by Rodolphe Lindt, who invented the conching technique for blending chocolate, improved the aroma and tempting melting qualities of the bars. It wasn’t until 1875 that that milk was introduced by chocolatier Daniel Peters, paving the way for our modern chocolate bar.

“Biochemically, love is just like eating large amounts of chocolate.“

John Milton