On June 28th a Bosnian Serb named Gavrilo Princep assassinated Austro-Hungarian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand, sparking a conflict that would slowly draw in all of the major nations in the world. The horrors of World War I would trigger a stark shift in global consciousness that would leave an indelible mark on future generations and essentially reshape the modern world. Innovations from the battles spanning 1914-1918 would redefine warfare for years to come. What many sociologists cite as a breakdown in the fabric of society would disrupt the status quo, leading to daring and sometimes dangerous new ideas that would germinate throughout the 20th century. While “the Great War” is often written off as merely the auditioning process for World War II, many of the facts we learn about this major conflict are easily proven false. Here are several key points about World War I that are often repeated but absolutely incorrect.

“Soldiers were living in trenches for prolonged periods of time”.

The mental image that most of us have when we think about the quintessential scene of the “Great War” is of men, living in the trenches, stuck there for long periods of time surrounded by rats, mud, decaying bodies and shell shocked men. This concept is so ingrained in the modern consciousness that it’s usually a shock to learn that on the average, the span of time spent manning a trench was only 4 days at a time. After serving in the trenches for 4 days, soldiers would be moved from the front line and spend for days in close reserve, then they would have 4 days of rest.1 So a unit would spend approximately 10 days out of a month in the trenches and quickly rotated to avoid demoralization from the exposure to the cold, wet and enemy snipers.

Being in the trenches meant hard work for soldiers who had to find a balance between returning fire to the enemy and maintaining the trenches and surrounding barbed wire. The work was tedious and physically demanding, as carrying dirt and digging was a constant job.

“It was the bloodiest war in history up to that point.”

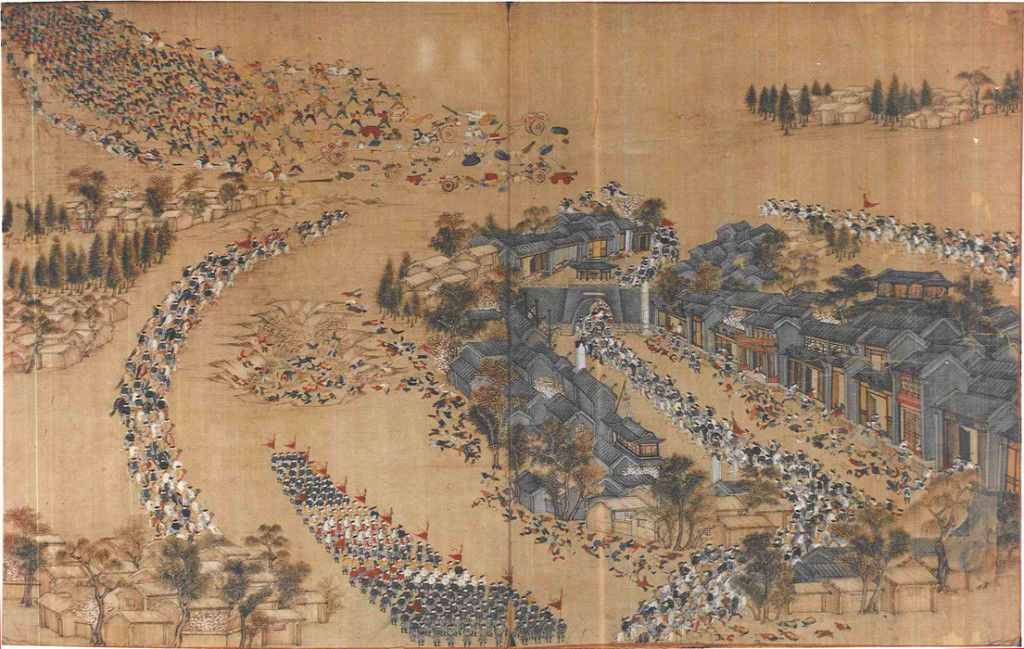

The estimated military and civilian death toll of World War I is around 15 million – a staggering number in comparison to other modern conflicts. While historians in the west often cite the Great War as being the bloodiest conflict up to that point, there was another war that took place in the east that left an indelible mark as the costliest in history up until the 1940’s. The Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) was a rebellion where the Hakka (a subgroup of the Han people) and the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom sought to overthrow the Qing Dynasty (a Manchu dynasty). While the Qing ruler would refuse to be toppled, the outcome of years of warfare left a death toll upwards of 20 million, with some claiming the number to be closer to 70 million.2

“The mortality rate of World War I was horrendous.”

For the British, who sent a little over six million men to fight in World War I, the death toll was a mere 750,000 lives lost. That puts their total losses at about 11.5%. As a comparison, a British soldier engaged in the Crimean War had a much bleaker future, as the death rate was over 22% for the British specifically.3 For Americans, the death rate was even lower, with only 117,000 deaths out of just over 2 million mobilized soldiers, making the prospect of surviving the war more hopeful for them than if they had fought in the American Civil War (where one in every 4 men would die).4

“We had been brought up to believe that Britain was the best country in the world and we wanted to defend her. The history taught us at school showed that we were better than other people (didn’t we always win the last war?) and now all the news was that Germany was the aggressor and we wanted to show the Germans what we could do.”

– Private George Morgan, British soldier

“The upper class soldiers were not expected to risk their lives like the poor men were.”

Another long standing misconception about the war was that the British working class would take the brunt while those of higher birth were kept safe on the sidelines. While those of more common birth were more likely to be seen as “canon fodder” it was the sons of the political and social elite that were entering WWI as junior officers. This meant that when the call was made to “go over the top”, young upper class men were leading the way, trying to embolden their men through a brave example.

The average soldier mortality rate was 12% – for officers, this number was 17%. Nearly 1000 former students of Eton College would die in World War I – nearly 20% of those who enlisted to fight.5

“The tactics used were antiquated and ineffective.”

Commonly people cite the antiquated tactics used in this war, without taking into account the larger scope of just how intense the “arms race” of the early 1910’s truly was for all the nations involved. Men took to the field with new and deadly innovations – and it was the task of their enemies to learn to deflect the devastation of these never-before-seen weapons.

Cloth hats were quickly abandoned for metal helmets. Whereas men had mostly been armed with rifles at the start of the war, they now wielded portable machine guns, flamethrowers and grenade launchers. The obstacle of “No Man’s Land” was conquered through the use of tanks. Tactics are constantly changing in response to new challenges and the armies adapted quickly to all the demands they met.

“Poison gas attacks took countless lives.”

Germans first used poison gas in Ypres, Belgium in 1915 – though they claimed that the British were already using mines charged with poison gas. In reaction to the use of the corrosive chemical, the New York Times described it as “… without doubt the most awful form of scientific torture.”

After experimenting with xylyl bromide (a poisonous organic agent that would be later used as tear gas) Germans switched to chlorine gas. Pleased with the effects, they added phosgene (a far deadlier gas) to the mix – finding it was 6 times deadlier than chlorine alone. Mustard gas, a potent blistering agent, was given the sickening title of “King of the Battle Gases”, and caused more casualties than all of the other gases, as it was heavier than air and would hug the ground and overwhelm trenches when released.6

While the threat of gas produced profound psychological effects on the soldiers in the field, reality is that it took very few lives. About 8,000 British soldiers died from poisonous gas attacks, whereas the United States lost 1,500.7 These mortality rates are low, compared to the number of men who were exposed to gas – but the effects of such attacks were potentially worse than the threat of death, causing severe suffering ranging from burns and temporary blindness to pneumonia and lung collapse.

“The Treaty of Versailles was unthinkably harsh on Germany.”

Prior to World War I, Germany was experiencing an economic boom. Between 1890 and 1913 Germany’s total exports had tripled – it was producing 17.6 million tons of steel, which was greater than Britain, France and Russia combined. It was also producing coal to rival that of Britain, and Germany’s share of world trade had increased from 17.2% to 26% during those years before the war.8 In the simplest terms, Germany was doing rather well for itself as compared to its European neighbors.

A few economic missteps made by the Weimar government during World War I would knock Germany from a comfortable and ever-expanding economic position, into post war poverty. The reparations to be made to the victors in the Versailles Treaty were nothing new – and were pretty standard for war treaties. After the Franco-Prussian War, Germany had demanded billions of marks from France for “indemnities”; while the money represented nearly 25% of the French national income, the French paid promptly. Germany was allowed to voluntarily comply with the terms of the treaty, and only expected to pay 50 billion out of the 132 billion marks to cover civilian damages inflicted by German soldiers.9

If anything, the Versailles Treaty was far more lenient than was usual – and for a country that had the economic power to easily repay the terms (had their governing powers not crippled the nation with bad financial choices), the punishment was mostly symbolic. The terms Germany had intended to impose on Allies, had they lost, were much more strict! The Germans were hoping to edge out their European market competition in World War I and have a quick war, like the Franco-Prussian War, where they would establish themselves as a world power. Yet, History did not play out as they had expected.

- Baker, Chris. “Life in the Trenches of the First World War.” The Long, Long Trail – Researching Soldiers of the British Army in the Great War of 1914-1919, https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/ Accessed 23 Nov. 2021.

- Corfield, J. (2011). Taiping Rebellion (1851–1864). In The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest, I. Ness (Ed.). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp1432.pub2

- McDonald, Lynn. “Florence Nightingale, Statistics and the Crimean War.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), vol. 177, no. 3, 2013, pp. 569–586., https://doi.org/10.1111/rssa.12026.

- Hirschfeld, Gerhard, et al. Brill’s Encyclopedia of the First World War. Brill, 2012.

- The National Archives. “The National Archives Learning Curve: The Great War: The Trench Experience.” The National Archives, The National Archives, 27 Jan. 2004, https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/greatwar/g4/cs1/background.htm.

- Everts, Sarah. Distillations: Using Stories from Science’s Past to Understand Our World, Science History Institute, 11 May 2015, https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/a-brief-history-of-chemical-war. Accessed 20 Nov. 2021.

- Pruszewicz, Marek. “How Deadly Was the Poison Gas of WW1?” BBC News, BBC, 30 Jan. 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-31042472.

- Gerald, Strauss. “Germany: The Economy, 1890–1914.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/place/Germany/The-economy-1890-1914.

- Chan, Amy. “Failed Peace: The Treaty of Versailles, 1919.” HistoryNet, HistoryNet, 6 Jan. 2020, https://www.historynet.com/failed-peace-treaty-versailles-1919.htm.

brianstammVerified

Great article. I have not read extensively on WW I however I plan on doing so in the future. This has incentivised me to do so.