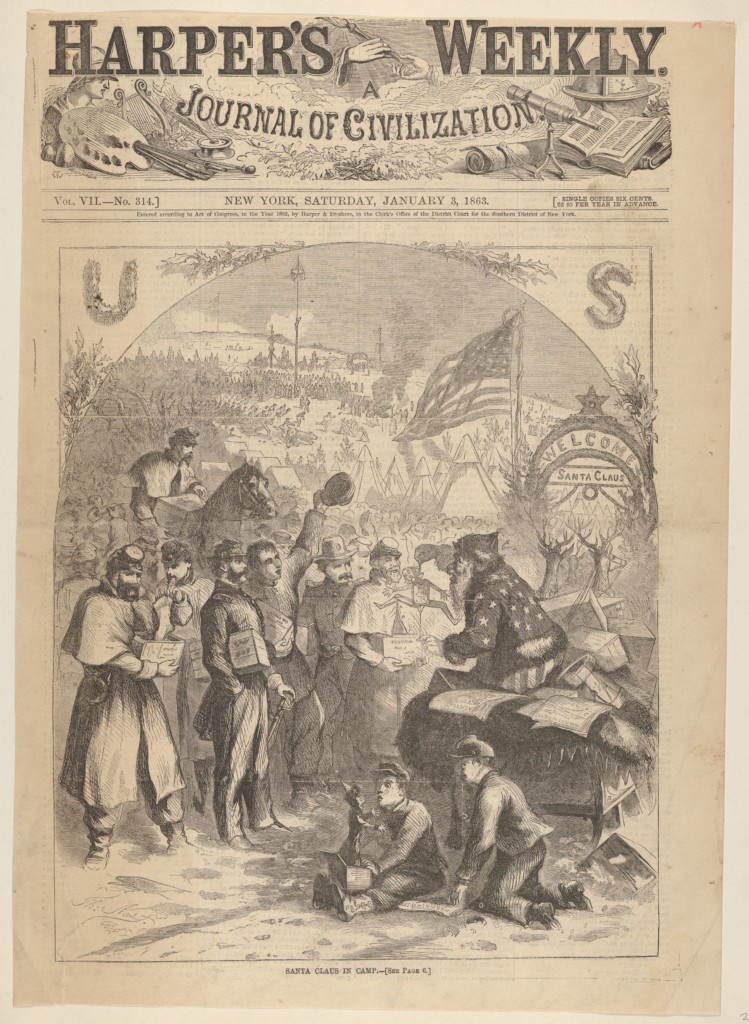

At this holiday time we all tend to find ourselves busy with decorating our homes, shopping for the perfect gift and running here and there for various items and foodstuffs to make the perfect Christmas. Many of us tend to sometimes forget the true meaning of the holiday and those individuals who are away from home and hearth serving in our armed forces. Their holiday experience in a foreign field, on board a ship or in a barracks of one of the many training forts scattered throughout the country may not be ideal. However, modern technology, such as cell phones and computers in which to video chat with loved ones, may alleviate some of the home sickness they may experience. Not so for the Civil War soldier. He had to rely on memories, comrades in arms, and if lucky a welcome letter, present or even newspaper from home to break through the melancholy associated with being away from loved ones. After all, Christmas is a time to celebrate with family and friends. However, despite the hardships associated with sometimes harsh physical and emotional conditions, the Civil War soldier, both north and south, found ways to make Christmas as enjoyable as possible.

For many of the soldiers in December of 1861, this was their first time away from home during the holiday and the harshness of war was still not ingrained in their minds. One southern soldier, who used the pen name “Clairborne” of the 12th Mississippi would write the Daily Dispatch in Richmond of how Christmas day was spent drinking eggnog toasts to the “permanency to the young Confederacy and good health to our glorious President” (Jefferson Davis). One of his counterparts, Private Frank Brunner of the 39th Ohio Infantry would pen after the war, that his first Christmas was spent outside of Syracuse, Missouri. Finding himself on guard duty with a foot of snow on the ground and “the wind blowing the snow into our faces”, he was delighted to find that the detail was allowed to stand inside of a local blacksmith shop. A fire was permitted to be lit in the forge to make it more bearable. As a further bonus the smithy was home to a cache of sutlers items, of which contained a bag of onions.

These turned out to be a welcome treat and permission was given to take a few. More than a few were consumed leaving an empty bag. Brunner wrote further that one of their reliefs procured the bag for use in his hut. Later, it was determined that the onions were to be used for sick soldiers in the regimental hospital. A search was conducted for the missing onions and upon finding the empty bag, officials arrested the unsuspecting culprit, who had not participated in the onion feast. The man was then placed in the guard house for his unrequited penance. Needless to say, he was visited by those who had participated in the larceny and was jokingly asked “how he liked onions”. 1

December 1862 would bring both northern and southern soldiers still wishing that the war would end soon. Confederate infantryman William McCabe would spend Christmas with his comrades writing a poem. He would include contemplation of the snow gently falling as he and his campmates sat by the campfire. The poem also included a few lines about his mother waiting at home upon his return…

“She fondly clasped her wayward boy

Face all radiant with the joy

She felt to see him home once more.” 2

Some of McCabe’s Union counterparts of the 1st United States Artillery near Beaufort, South Carolina would celebrate by participating in games of climbing a greased pole, feats of strength and horsemanship as well as artillery and pistol practice. A reporter from The New South would pen “After the games came feasting and jollity and abundance of good cheer was consumed in honor of old Saint Nicholas.” Not to be outdone, the Provost Marshall in camp organized a baseball game and later a minstrel show.

Failures of the Confederate armies at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in July of 1863 would still not dampen the southern resolve to break away from the north. Despite a rampant inflation on the cost of southern goods, members of the 12th and 14th Virginia, assigned to garrison duty in Petersburg, would receive from the city’s citizens a bounty of “400 turkeys and an equal number of fowls” as well as citrus fruits, numerous types of vegetables, candy, ham, Christmas cakes and various ardent spirits in order to celebrate the 1863 holiday. Meanwhile on Morris Island, South Carolina, Union troops celebrated with “batteries opening on Charleston” Christmas Eve. A large fire began in the southern part of the city “setting the cradle of Rebellion in flames”. One would think that enough fighting had been satisfied and a truce called for the holiest of holidays. Such was not the case. 4

By Christmas of 1864 the war was beginning to take its toll on veteran soldiers. The southern economy was in a shambles and the Confederate government was struggling to supply its armies in the field. An officer under Confederate General James Longstreet would pen a letter home while outside of Knoxville, Tennessee. He would write of his Christmas dinner consisting of only beef and bread and pray for the commissary in the New Year to supply “something more palatable”. He would go on to say that the local residents, being northern sympathizers, had an abundance of supplies but the southern soldiers were on “half rations”. 5

Meanwhile, Union troops were well supplied and despite being the 4th Christmas of the war, celebrated with abundant fare. Soldiers at Alexandria, Virginia’s Fort Barnard were able to sample delicacies such as turkey, chicken, goose and duck as well as all of the trimmings at the 3rd Brigade’s “restaurant” for “reasonable prices”. Private Frank Brunner, the Ohioan soldier whom we met earlier, would invite several members of the 83rd Ohio Infantry to partake in “something stronger than water” to go with their Christmas meal. Even Union troops convalescing at Summit House Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania would be the beneficiaries of a bountiful feast. The food would be supplied by the facilities manager and his wife, Dr. and Mrs. Egbert, and a donation of almost $3000 to help cover the almost $5000 cost of the meal. 6

Donations from local citizenry for southern soldiers would dwindle as the war progressed due to the collapsing economy. The United States Sanitary Commission, a northern Christian run organization, would benefit soldiers from that side as well as gifts from home and even large donations from some of the north’s cities added to assist the wounded in various hospitals. For example, in 1862 a large number of provisions consisting of “turkeys, chickens, apples, cranberries, oranges” and other food would be sent to hospitals around the US capitol in Washington, DC from northern cities. This process would continue until the end of the war. 7

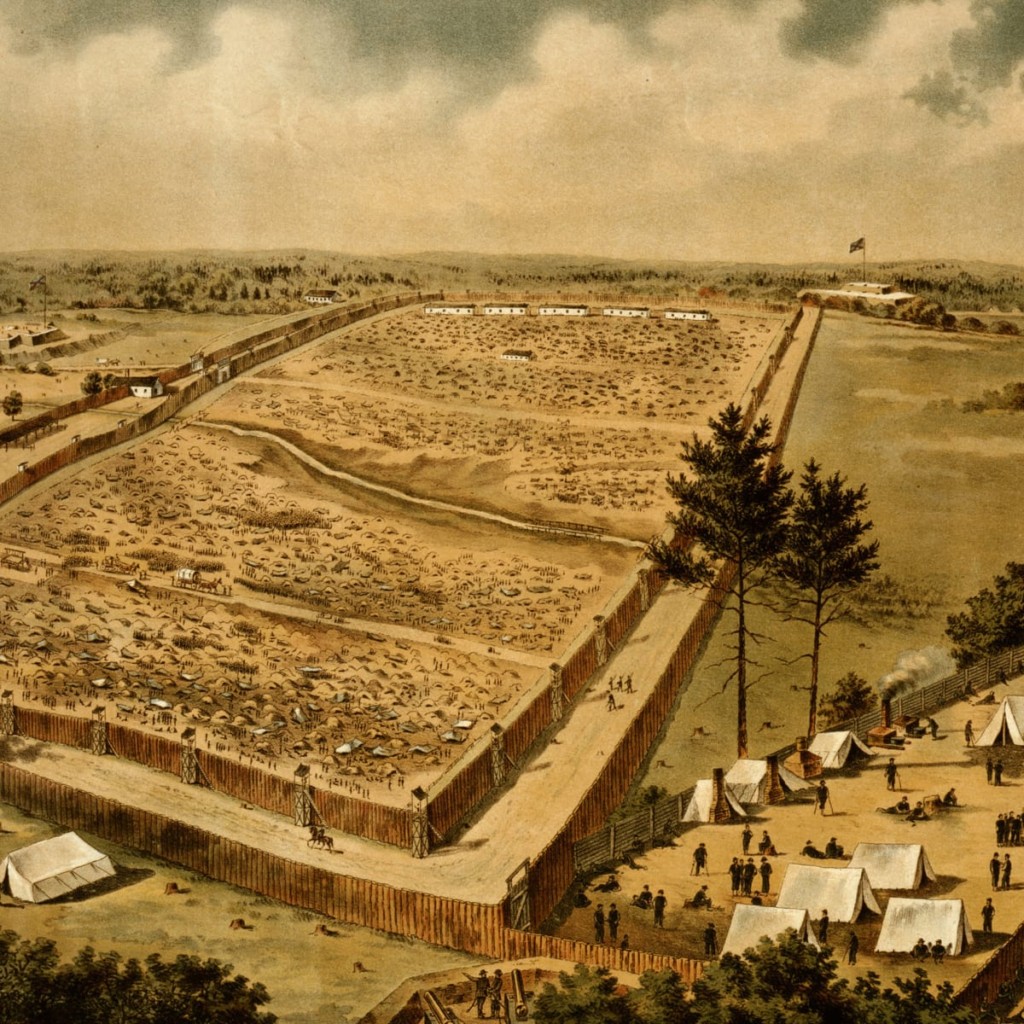

One group of soldiers who would not benefit from the kindness of local citizens, large city donations or the US Sanitary Commission would be those who were prisoners of war. Both northern and southern prisons left much to be desired. Filth, food shortages and poor sanitation as well as disease would lead to numerous deaths in those institutions on both sides until the end of the war. Lt. John Blue of the 7th Virginia Cavalry would spend the Christmas of 1863 at the infamous Johnson Island prison on Lake Erie. Having to share a bunk with a brother officer, the extreme cold conditions, at times reaching 40 below zero, lack of warm clothing and firewood as well as poor food, made his stay there difficult. As conditions worsened, he and his comrades subsisted on rats and an occasional dog in order to supplement their meager rations. Blue would eventually be transferred to Fort Delaware in June of 1864. However, the brutal cold had done permanent damage in the form of rheumatism in his feet, making him lame for the remainder of his life. 8

Two northern prisoners would also recount their Christmases in captivity, the first one being in the notorious Andersonville prison. 1st Sergeant J.S. Lemmon of the 5th Iowa Cavalry would write, post war, of his “second” arrival at Andersonville on December 24, 1864 and how the long cold march to Andersonville from Camp Lawton near Savanna, Georgia dampened his holiday spirit. He and numerous others had been transferred from Andersonville earlier in answer to General William Tecumseh Sherman’s march through Georgia. Another soldier, listed only as E.H.W., would also pen after the war, about his holiday stay at Florence stockade in South Carolina. He was another who had been transferred from Andersonville in response to Sherman’s Georgia arrival. E.H.W. had been detailed to work outside of the prison as a wood cutter. Getting his work done quickly, he proceeded to slip away to a field abundant with “black cow peas”. Tying strings snugly over his trousers around his ankles, he hurriedly filled his pant legs up to his knees and then filled his pockets with more of the peas. Returning to the work detail, he discovered that they had returned to the prison. Fearing a severe punishment for his absence, he immediately started for the prison. Upon arriving at the gate, he was accosted by the guards but was eventually allowed to take the bounty inside. He and his friends borrowed a kettle and by noon on Christmas day sat down to feast of their “first good meal in six months, there was more joy and satisfaction over it than could be obtained from many a more sumptuous repast under other circumstances”. 9

Spring of 1865 would be the beginning of the end of Confederate armies across the country. Robert E. Lee would surrender to Ulysses Grant at Appomattox, Virginia on April 12 and the final surrender would occur at Doaksville in the Indian Territory on June 23 of that year. There would still be one final Christmas that some soldiers would endure away from home, but not on the battlefield. Those individuals were the unfortunate wounded who still languished in the numerous military hospitals across the country. The last Civil War Hospital to close was Harewood Hospital in Washington, DC. Harewood’s doors would not be locked until May 5, 1866 as its final patients returned home.

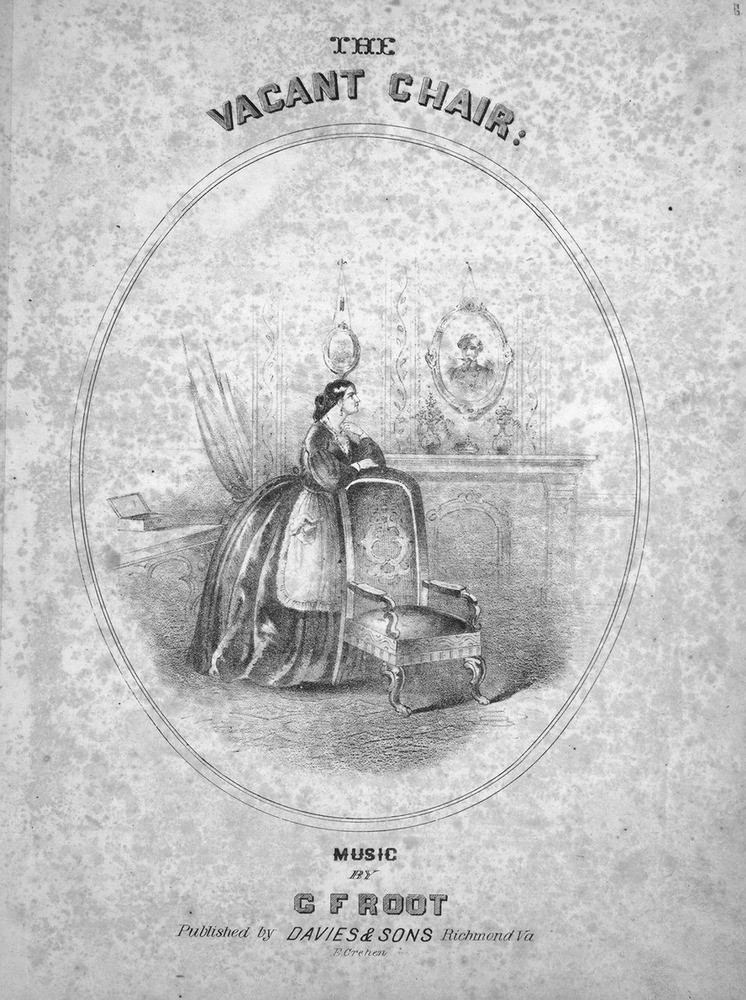

Around 620,000 soldiers would never make it home to their families after the close of the war leaving many an “empty chair”, ala Charles Dickens, around future holiday tables. More soldiers would die during the Civil War than all other United States wars combined until the war in Viet Nam. The cost of war was indeed high. Hopefully those fortunate enough to return home after the war would come to cherish future Christmases in the bosom of their loved ones and friends. Unfortunately, those empty chairs would serve as a constant reminder of the loved and lost, both on and off the battlefield, for many future Christmases to come. 10

1. The Daily Dispatch, Richmond, Va. December 31, 1861, page 2: The National Tribune,

Washington, DC. December 28, 1899, page 3.

2. McCabe, William, Christmas Night of ’62, American Battlefield Trust web post.

3. Sears, Jos. H. Editor, The New South, Port Royal, South Carolina, December 27, 1862 page 3.

4. Alexandria Gazette, Alexandria, VA December 30, 1863, page1; The New South, Port Royal, SC

January 2, 1864, page2.

5. The Abingdon Virginian, Abingdon, VA January 1, 1864, page 2.

6. The National Tribune, Washington, DC, December28, 1899, page 3 and March 28, 1901, page

8; The Soldiers Journal, Rendezvous of Distribution, VA, December 21, 1864.

7. The Daily Dispatch, Richmond, VA, December 31, 1861, page 2; Alexandria Gazette, December

24, 1862, page 2.

8. Blue, Lt. John, Hanging Rock Rebel, (Edited by Dan Oats), Beidle Printing House, Shippensburg,

PA 1994, pages 247-252, 279, 282 and 302.

9. The National Tribune, Washington, DC February 25, page 3 and March 4, page 3, 1889.

10. Prologue Magazine, Spring 2015 Volume 47, No. 1, National Archives, Washington, DC page

24; Price, Angel, Whitman’s Drum Taps and Washington’s Civil War Hospitals, February 19.

2019, The Capitol Project, Charlottesville, VA, page 13.

Image of Civil War Soldier’s Mess from the collection of the Smithsonian

NiobeVerified

Thanks for sharing this article! I always feel bad for the soldiers who were on the younger side of the average (25 years old for the Union was average) who were away from home during the holidays. It seemed to be well-illustrated in that Harper’s Weekly cover with Santa Claus. Many would be considered kids by today’s standards.