With gentle fingers, he sets the slippery clean china on the cloth to dry. He’s kicked down hay from the loft for the cows, fed the pigs and fierce, yellow, Spitz dog who guards the farm. The cows have been milked one by one, as he hums soothingly in the early morning light. He stokes the hearth fires. What had set him off three days ago? It’s hard to tell now, as he calmly goes about another man’s chores. It will be another full day until the bodies are discovered at a small Bavarian farm called Hinterkaifeck.

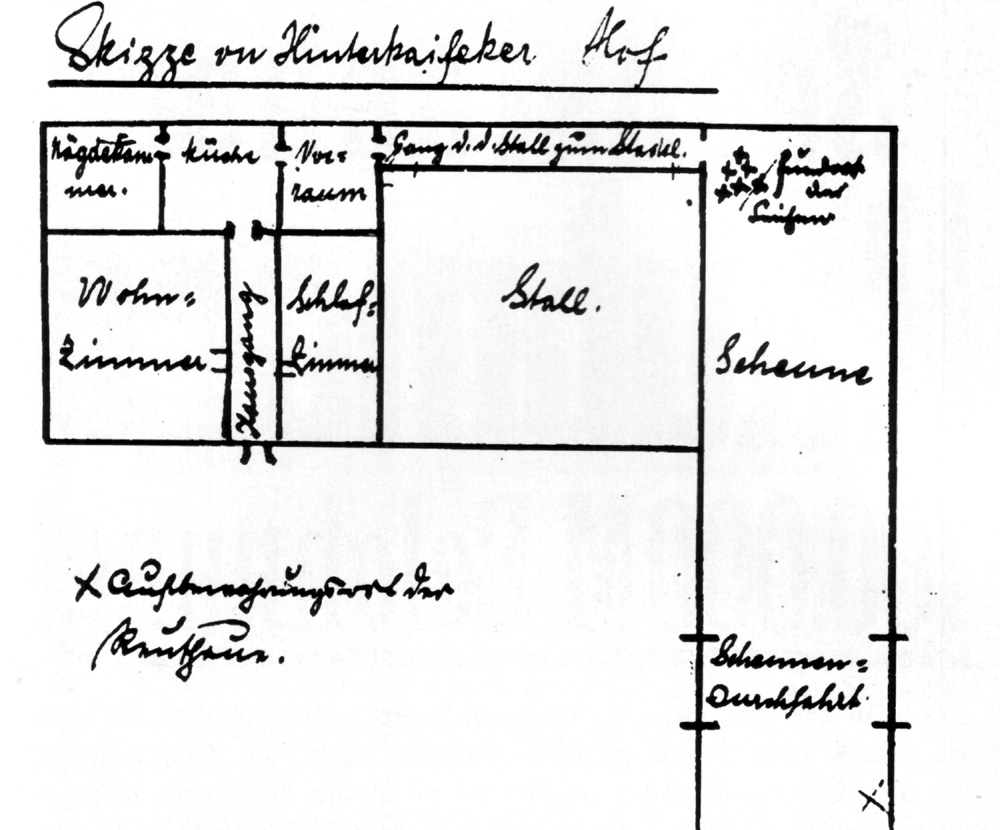

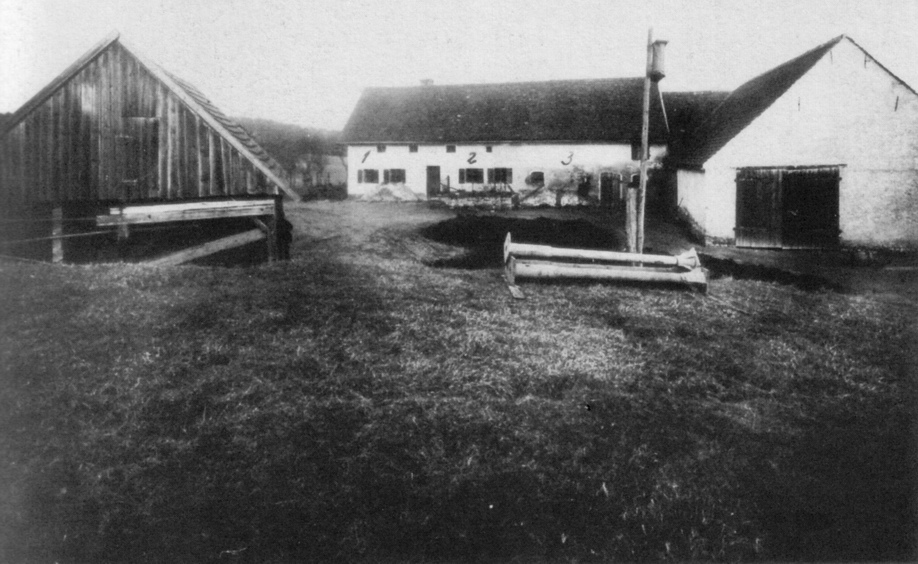

Hinterkaifeck is translated literally as “Behind Kaifeck”. Kaifeck was a very small group of farms, separated by expanses of fields and strips of woodland. The nearest settlement was Gobern, which lay almost a mile away. Hinterkaifeck lay at the edge of the populated areas, considerably isolated from even the closest neighboring farmsteads.

March 31st, 1922:

Andreas Gruber sits down to dinner with his wife, Cäzilia, widowed daughter Viktoria and her two young children. He is a quarrelsome, miserly man, shunned by most for violent threats to neighbors and his conviction for incest with his daughter. A new maid has arrived that day, named Maria Baumgartner, to replace the last maid who quit over fears of ghosts in the attic. Andreas is not concerned with ghosts; he has confided in his neighbor about the strange instances and his suspicion that an intruder was in his house. Keys were missing, locks damaged, footsteps heard overhead through the night, and a set of tracks discovered in the snow, heading towards the farmstead, but not away. When his neighbor, Lorenz Schlittenbauer, offers him a gun, Andreas refuses.

“…He feared that something was wrong in his house. He further said, ‘There has been no rest during the past night, all night I heard something up in the attic, like someone walking around. I also went up with a light, but didn’t see anything. I am not afraid… In the morning I even saw a track in the fresh snow that led into the house, but I didn’t see a track that led away from the house.'”

From the Police Statement of Bley Wenzeslaus

In the village on March 31st, Viktoria also mentioned in passing that she heard footsteps on the floor above her rooms at night. The construction of the farm incorporated a long attic space that spanned the entire house and barn. It was possible to access the attic of the living spaces by way of the barn.

Earlier that day, Gruber took a light and searched the attic space. Upon inspection, he found there was a large amount of hay moved and spread across the entire attic floor; this “Heuteppich” was placed as if to muffle footfalls. Seemingly indifferent to the worrying indications that they may not be alone in their own home, the family kept to their usual routine as night fell.

After dark, events unfold that would forever transform Hinterkaifeck into the topos for unfathomable evil.

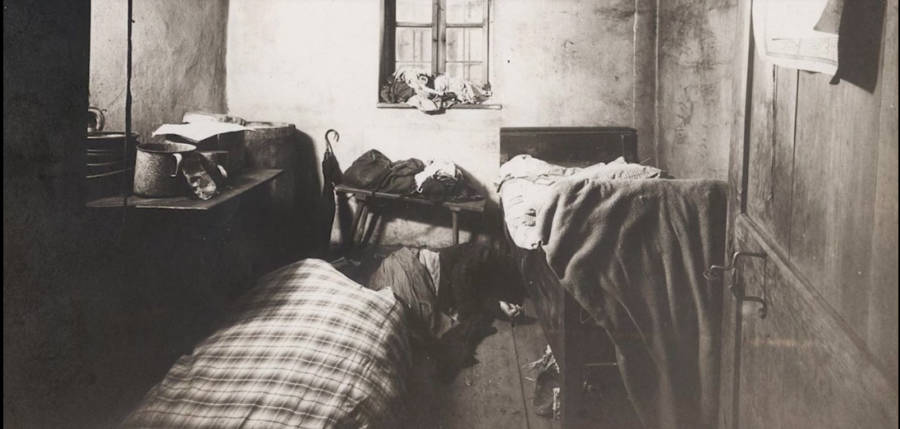

The new maid was shown to the closet that had been converted into a bedroom; she did not even unpack her belongings. The youngest of Viktoria’s children, a 2 year old named Josef, was asleep in his bassinet. Her daughter, named Cäzilia after her grandmother, was undressed put to bed in the room she shared with Viktoria. It is surmised that Andreas went to bed before his wife and daughter turned in for the night.

Late Hours of March 31st – April 1st, 1922:

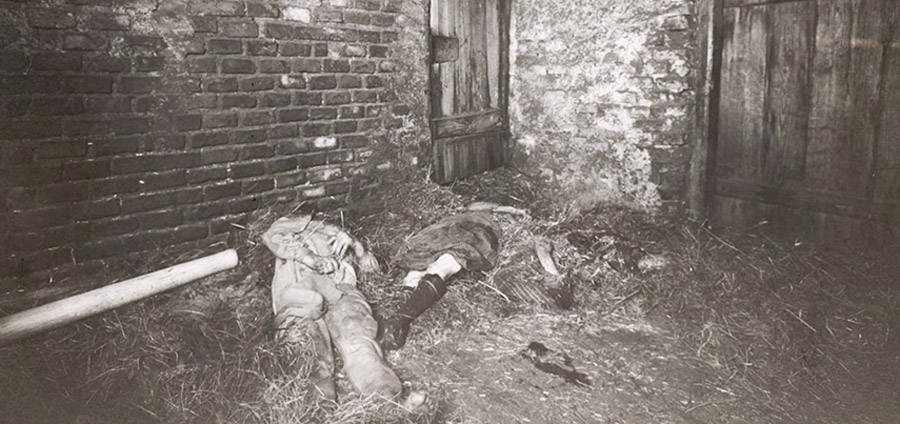

In the early hours of April, the family was lured one-by-one into the barn. The entire household would be butchered that night, by an unknown murderer for an unknown reason.

What drew them? Perhaps a cow was let loose in the courtyard. In the days leading up to the murders, Gruber and neighbor Johann Krammer had cattle escape under strange circumstances. Was it a practice run?

The old Cäzilia was first, felled with seven blows to her head; then Viktoria, who received nine “star shaped” wounds to the head, the right side of her skull caved in with a blunt object. Both women were both fully clothed and showed signs of overkill and strangulation. It is theorized that Andreas was next, roused from his sleep, as he was found in his underpants and shirt with the right side of his face smashed, his flesh cut away so that his cheekbones were visible. Then young Cäzilia, who was only 7 years old, possibly seeking her mother with whom she shared a room. Her jaw and skull were shattered and there was a long transverse wound at her throat (made by a penknife) – she remained alive but incapacitated for several hours in the pile of bodies, under a thin layer of hay the killer scattered over them.

The weapon used was a reuthaue, a brutal farm implement that would have been found close at hand. This same reuthaue was stolen by Andreas Gruber from Lorenz Schlittenbauer (the man who had offered Gruber his old army revolver for protection). While often described as a mattock or pickaxe in English, the reuthaue was a lighter, easy-to-wield instrument with a blunt metal edge and protruding screw for causing “brain death” when dispatching pigs.

The killer reentered the house. He killed the maid in her room with crosswise blows from the mattock. Finally, he found the toddler in his bassinet; a single blow extinguished the child’s life. An attempt to dig graves for the bodies was abandoned due to the frozen ground, coated with ice from a storm that night. Instead he covered the face of the maid and child with clothing, depersonalizing them to defuse what can only be assumed was some emotional response, and went about living a shadowy existence in the farmhouse for 4 days.

“Why the murder or murderers also killed the 2 year old boy, one cannot quite explain when this child presented no danger…”

Georg Reingruber, police detective investigating hinterkaifeck in 1922

Who was this killer, that in one moment lived hidden in the attic and in the next brutally killed an entire household, before returning to a quiet sort of existence among the dead?

Police found evidence to suggest that the villian had been living within the attic of the farm for some time – if the previous maid was correct in her assessment of the “ghost” on the floors above, he might have been in the house for some months. The attic ran the entire length of the living space and the barns, meaning that a person could enter through the barns and move across the entire floor plan of the farm, undetected. Chewed up bacon rinds were hidden in the attic along with a pile of human feces confirmed this suspicion to police – they also found a rope was hung from the attic hay loft for easy access from the barns below. A few of the tiles from the roof had been loosened, creating an ideal vantage point to watch the movements in the farmhouse courtyard down below.

After the murders, the unknown man was helping himself to smoked meat and freshly baked bread, sleeping in one of the family’s beds, cleaning up after himself in general and also doing all of the farm chores. One of the reasons that neighbor’s didn’t check in on the family even with them being absent from church and school was that there was smoke billowing up from the chimney, signalling that all was just as it should be within the house.

The contentedness of the animals was remarked upon by passersby after the fact.

“The people, like the postman, as well as Blöckl, who passed by at night, did not hear the screaming of the cattle. It is assumed that the man who was observed by Blöckl at night fed the cattle.”

From the Police Statement of Bley Wenzeslaus

Only the Spitz dog seemed worse for wear when spotted by neighbors on the property, having a large gash across its face and both cowering and snarling at any who approached. For the most part, the murderer took good care of the farm for several days. He was even spotted the night after the murder, when carpenter Michael Blöckl was walking past the farm on his way from Gröbern to Mitterhaid. Someone was operating the bake oven in the courtyard, the light illuminating the figure in the darkness. Upon spotting Blöckl, the unknowns man shut the oven door, walked over and shined an electric flashlight right into the carpenter’s eyes for a few moments, before silently walking back to the oven. The event left Blöckl unnerved, and he ran away as quickly as his legs could carry him.

April 4th, 1922

On the fourth day after the murders, a fitter named Albert Hofner arrived at Hinterkaifeck. He had been hired to repair a head gasket on the Sendlinger 4 HP petrol engine in the shed, and though no one answered the door when he knocked, he decided he would just get on with his work. By the time Hofner had finished, he noticed the barn door was now standing wide open, and that the dog had been moved and tied to the front door. Upon trying different ways to access the house, he found it was locked up. Hofner eventually left, but soon came to realize that he had been working a few meters away from the murder victims.

Hearing rumors about the strange quietness of the farm, neighbors would decide to investigate in the evening on April 4th. Lorenz Schlittenbauer, along with Michel Poell and Josef Sigl were the first to spot the pile of bodies in the barn. Schlittenbauer then quickly made his way into the house, desperately trying to find the youngest child, who was supposedly his own (he had an affair with Viktoria and was paying to support the child, but the parentage of the boy was always in question, do to Andrea’s incestuous ways). When he reemerged from the house, he mourned for the child for a few moments, then pulled himself together. Within hours, word had spread about the horror at the Hinterkaifeck farmhouse and crowds of people began to gather. Schlittenbauer did something rather inexplicable, in light of his grief and connection with the victims: he began giving tours of the murder scenes in the house and barn, allowing dozens upon dozens of people to trample vital evidence.

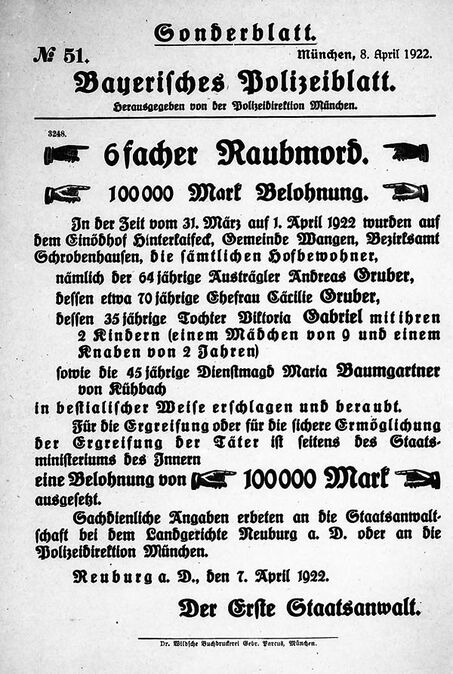

When police arrived, they had only a few hours to make their investigation. They were overwhelmed with a string of politically fueled feme murders in the area and had very few resources to help when such a horror occurred so far from their base in Munich. Oddly enough, one of the detectives had the heads of the victims removed to be sent to a clairvoyant in order to divine the identity of the killer- the result he reported was “negative”. At the time, they couldn’t even find the exact murder weapon. What data they collected was mostly lost during WWII, including the official autopsy report (if one was even made), the preserved heads of the victims and many of the original witness statements. The list of suspects was long – but in the end none were convicted of the crime.

“The murder of Hinterkaifeck is long a well-known platitude of horror, a topos for the primal experience of evil, the merciless deep in the homeland strikes and leaves an eerie inexplicability in its wake. A cipher of the eternally mysterious in a rational world.”

Christian Silvester, Hinterkaifeck: ein Kriminalfall mit 6 Toten, der die Menschen bewegt

The Years That Followed…

In years that pass, theories will abound from the supernatural to political killings, and a morbid fixation steeps the event in mythic status. Yet the Hinterkaifeck killer is never caught. Demolition of the farm in 1923 revealed the reuthaue, a folding pen knife and an iron hoop hidden under a false floor by the main fireplace. Lorenz Schlittenbauer, who was a suspect in the case at one time, lost his extensive collection of notes on the case in a house fire in 1926. Though the facts are erased by time, Hinterkaifeck lives on, an undefeated mystery set against the stark deprivations of post-WWI Germany: who was he?

brianstamm

Just from the text, I would suspect Schlittenbauer as the primary suspect. I’m fairly sure, if they had had the technology and forensic science then that we do today, this one could have been solved. Another great article Niobe.

Niobe

Schlittenbauer (or “the Sledge Maker”, as the reports all called him) was a suspect at the time of the crime and many people still believe he was the murderer. There are plenty of reasons he’d fall under suspicion.

He accessed the locked house after the murder using a key. Other witnesses said they were not surprised that he had a key to the house, as his status as Viktoria’s lover was common knowledge and having a key seemed natural. Only later did this key seem very suspicious.

One argument against Schlittenbauer is that he had his own farm to run and because of this couldn’t be absent for the amount of time reflected in the evidence indicating a person lived in the house for those days.

Very hard to know! Schlittenbauer had motive and means!