On the farthest edge of color waves visible to humans, there is red.

It evokes a range of complex meanings and ideas: love, anger, risk all come to mind upon glimpsing it. Over the course of history, it’s become a symbol for concepts both real and abstract. It is used to represent sacrifice, luxury, passion, and victory – though darker meanings are also affixed to red, namely authority, war, desire, guilt and evil.

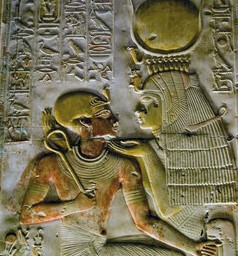

“O Isis… deliver me, set me free from all bad, evil red things!”

— An Ancient Egyptian prayer from c 1700 B.C.

Red is splashed across our consciousness, taking forms of the highest good and greatest evil.

It is difficult to feel indifferent about red. Red commands the eye. For a large portion of history, this shade was as elusive to produce as it was coveted. Herbs and minerals often produced what is called “fugitive colors” – meaning that their original tones soon faded or washed out into pale pinks and browns. The coveted shade was True Red – a “primary” color; a vivid crimson; the same color that flowed from an opened vein. This gallery is an exploration of the quest for red, it’s use throughout history and it’s impact on modern viewers.

Red Ochre

Many of humanity’s first attempts to attain red have been lost to time, but one of the earliest brick-toned pigments used has remained untouched by light or weather for over 285,000 years. When Paleolithic peoples recognized the lasting qualities of red ochre, a natural clay pigment made from iron oxides (hematite), they utilized them extensively to blanket graves with color, decorate and adorn their skin and create vivid images on cave walls. At Cueva de las Manos, in Argentina, red ochre clay was liquefied, held in the mouth and expelled through specially made bone straws that aerated the pigment, creating a fine spray of color. It essentially worked like a stencil, using the hand as a resist and the cave wall as a canvas.

Depending of on the geographic location of the the ochre, it’s colors ranged from yellow to purple to red. Heating of ochre would darken it’s tone to a deep, dark red, creating what is perhaps one of the reds used longest throughout history. The ancient Egyptians used red ochre to designate men from women in their renderings – the color was used extensively through the Renaissance with raw hematite-laden chalks dug out if the ground, sharpened and used for sketching. By the 19th century, iron oxides were being artificially formulated in laboratories, creating Mars red.

Vermilion

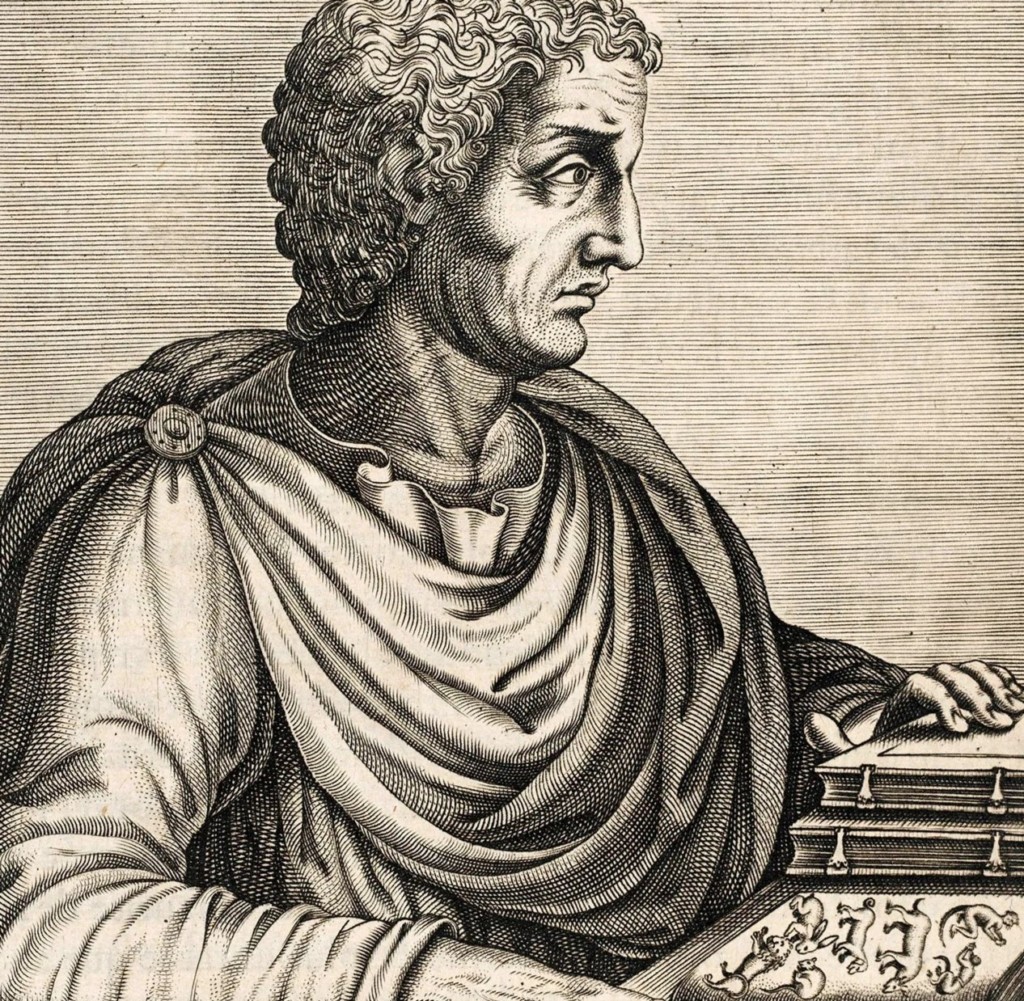

One of the truest, brightest and lasting reds available in the ancient world was produced from cinnabar. This pigment, called vermilion, was produced by finely grinding mineral mercuric sulfide – it was favored by the Romans, who sent prisoners and slaves to their death, working the toxic mines of Almaden. Cinnabar was an indicator of wealth, and as demand rose it’s price had to be controlled by the Roman government to keep it from becoming impossibly expensive.

Examples of decadent use of red can be seen in the frescoes in the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii. Working with such precious materials proved to be too tempting to resist, as Pliny the Elder describes; and by frequently washing their brushes in water they later secreted away, the fresco artists of the Villa of the Mysteries stole a substantial cache of red.

“Nothing is more carefully guarded. It is forbidden to break up or refine the cinnabar on the spot. They send it to Rome in its natural condition, under seal, to the extent of some ten thousand pounds a year. The sales price is fixed by law to keep it from becoming impossibly expensive, and the price fixed is seventy sesterces a pound.”

— Pliny the Elder.

Chinese Vermilion

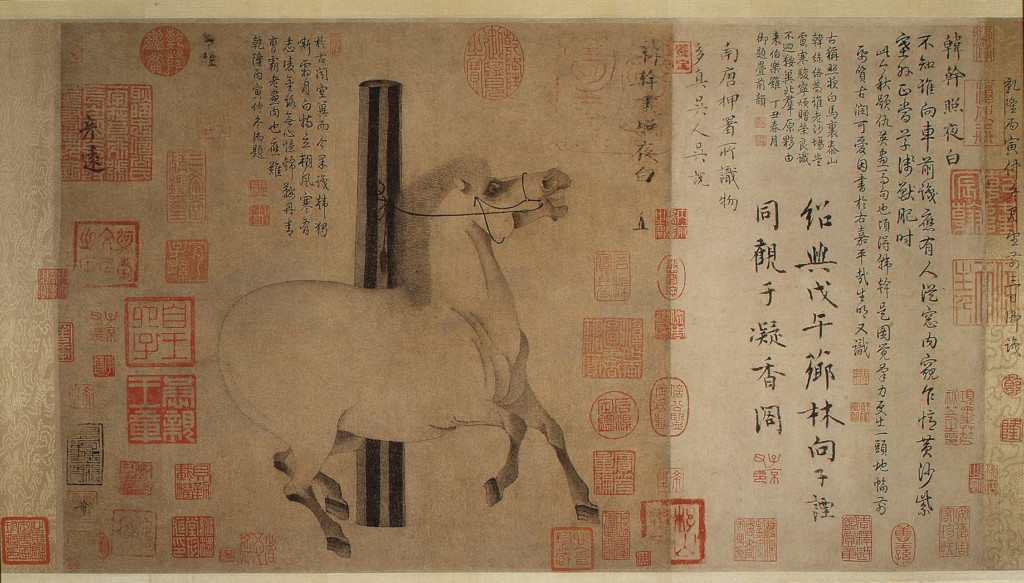

Ancient authors referred to the pigment created from cinnabar as vermilion – but prior to the Middle Ages, the Chinese formulated a synthetic shade that was also called vermilion (Chinese Vermilion). The orange-tinged red of Chinese vermilion had one drawback: it was a fugitive pigment. It was prone to deterioration as exposure to sunlight caused it to darken to black, whereas true cinnabar vermilion remained permanently bright, most vibrant of reds.

In Asian culture, red is one of the most auspicious of colors, where is symbolized joy, good fortune and was also believed to have the power to ward off evil. The use of red seals to sign art and designate ownership of art started during the Shang Dynasty (1600 to 1049 BC) – the seal paste (zhūshā) was almost always exclusively red.

Han Gan’s portrait of Night-Shining White, a charger belonging to Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–56) is covered in over one thousand vermilion-hued seals, indicating it’s importance and long-running impact of what may be the greatest equine portrait in Chinese painting. The number of red seals greatly elevated the value – as well as the virtue – of the art they adorned. The horse itself was one of the “Celestial horses” was was prized for it’s characteristic red, blood-drenched sweat upon exertion – they were believed to be dragons in disguise, bringers of wealth and luck.

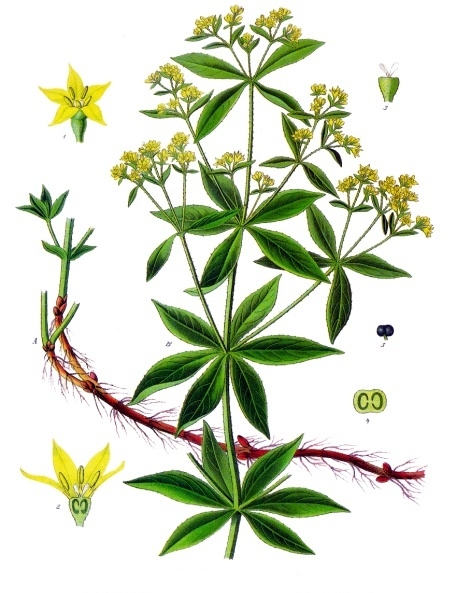

Madder Lake

One of many organic reds used antiquity was derived from the roots of the Madder plant (rubia tintorum). Scraps of madder dyed fabrics have been found in the tomb of the pharaoh, Tutankhamun – it was also widely used by the Greeks and Romans. By the 13th century, madder was being cultivated on a fairly large scale across Europe – all in the pursuit of the perfect scarlet hue.

This same purple-tinged red dye was later “laked” through the addition of potash alum, creating madder lake. Though it is derived from an organic dye, madder is one of the more stable of the natural pigments – and it’s unique, transparent qualities made it indispensable to painters in the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

X-radiograph images of van Eyck’s paintings reveal the manner in which the artist layered three coats of transparent madder lake over other reds, achieving depth and adding to the 3-dimensional quality of his fabric draperies and enhancing the richness of their tones.

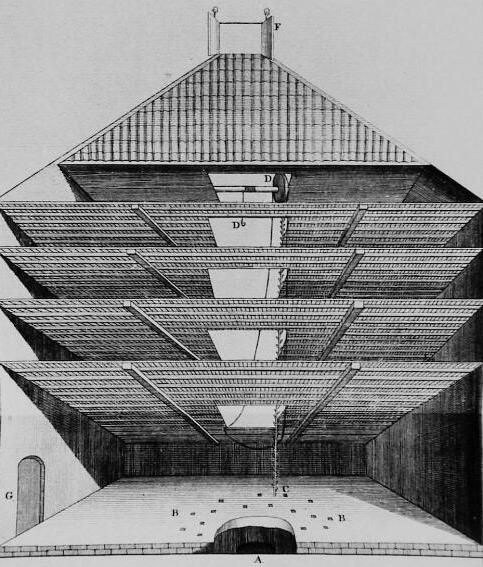

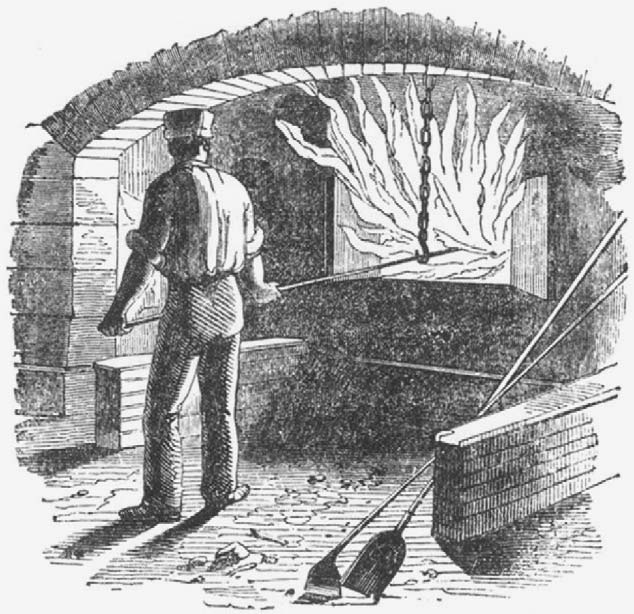

Minium (Red Lead)

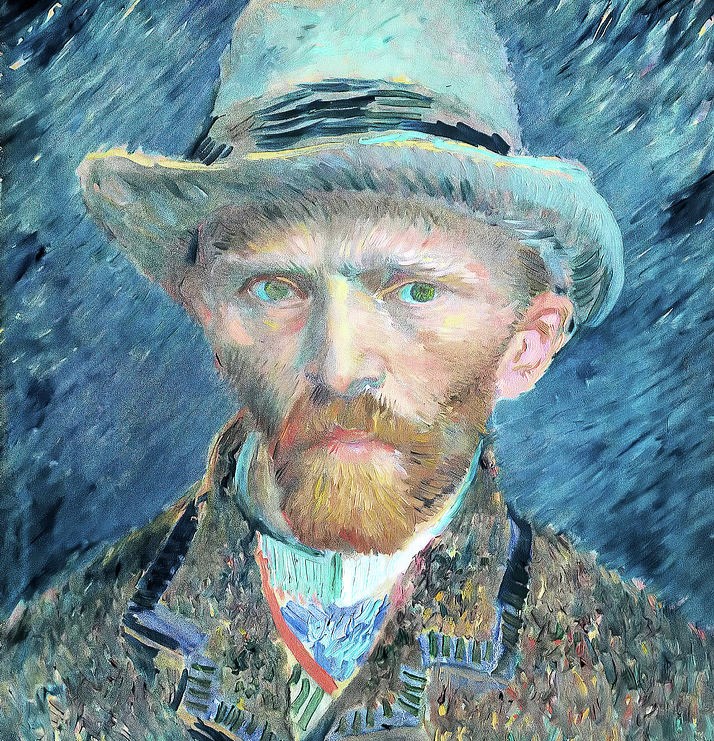

One of the first synthetic red pigments was produced by the Romans, who took white lead and heated it to high temperatures, making minium, also called red lead. Producing minium was highly toxic – carelessly handling its powdered form could result in death. While the pigment had fugitive qualities and tended to fade to white with light exposure, it created an inexpensive, vivid hue. It favored by medieval illustrators in manuscript illuminations (which is no surprise, seeing as vermilion cost the same as gold leaf at the time) and Mughal artists of the 17th and 18th centuries. Red lead was also used by artists in the 1800’s – including Vincent van Gogh.

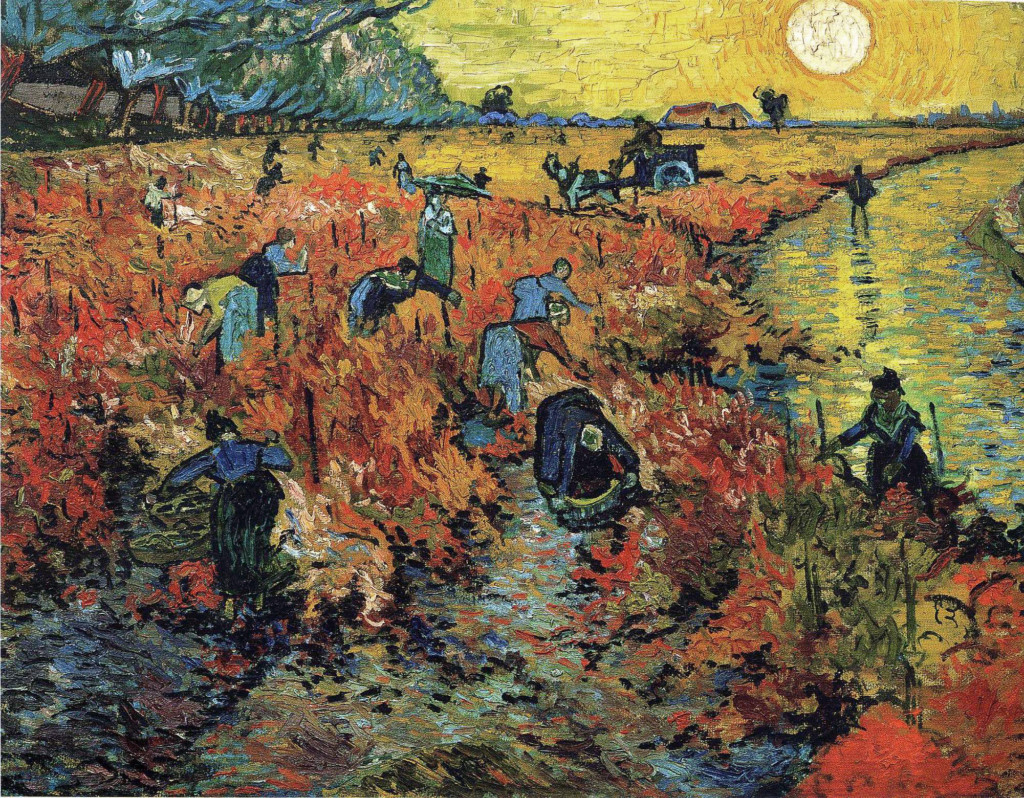

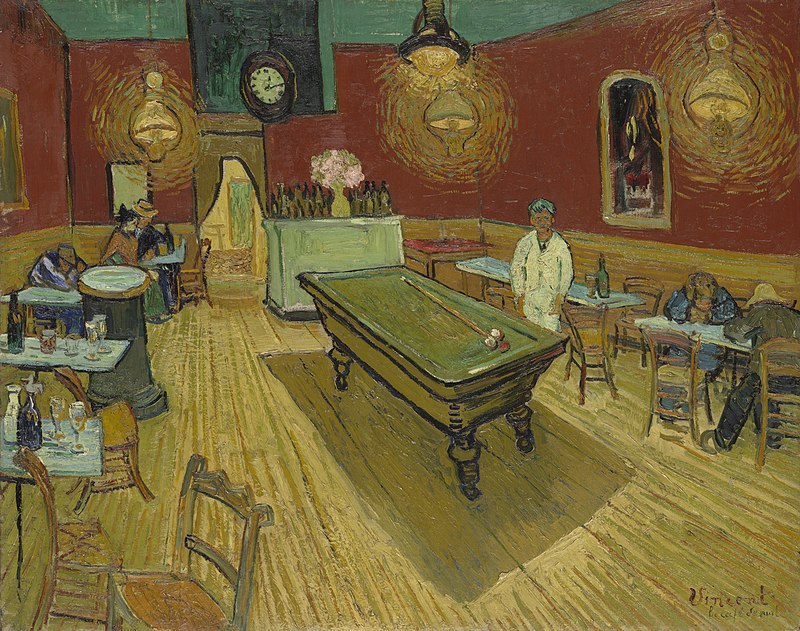

Van Gogh understood the symbolic power of colors, using them to express the emotions that brimmed within him – often he used red lead paired it with it’s color contrast, green. The blood red hue of minium added tension to his radiant palette, as the artist loaded his paintings with suggestion: “I tried to express through red and green the terrible passions of humanity.” Van Gogh’s treating physician, Dr. Peyron, described the artist eating his lead-based (red minium) paint in an attempt to poison himself – the very characteristic scintillation and halos of natural and artificial light seen in his paintings may have been a result of swelling of the retinas due to lead poisoning which caused van Gogh to see glare from light sources.

“Painting it was hard graft… in addition red, yellow, brown ochre, black, terra sienna, bistre, and the result is a red-brown that varies from bistre to deep wine-red and to pale, blond reddish… ”

— Vincent van Gogh