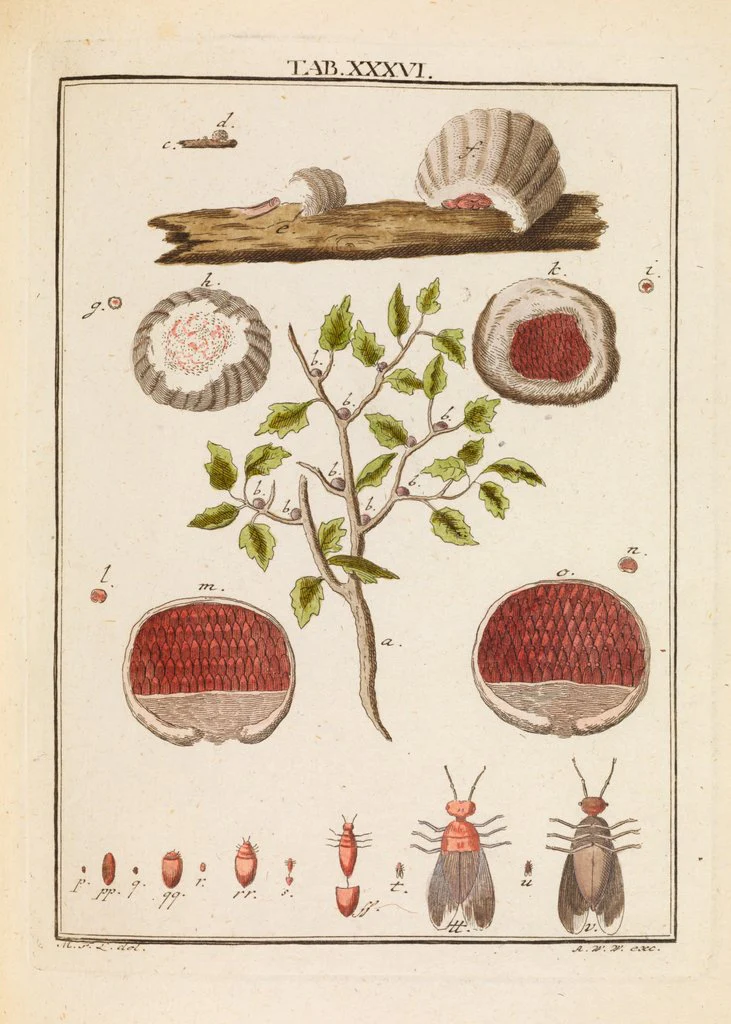

Crimson (Kermes)

Crimson red was another blood red pigment used since ancient times, harvested from the dried insect, Kermes vermilio. Crushing the scale beetles would result in a rich orangey-red stain; it was called the “King’s Red” as it surpassed Tyrian purple in both it’s cost and prestige. The kermes or crimson red was colorfast when used to dye wool and silk and was used exclusively in the medieval European manufacture of “Scarlet” (a finely woven woolen luxury cloth dyed in red).

The desiccated insects closely resembled grains, which is why they were referred to as “grain” in most Western European languages. Red was the chosen color worn by royalty and cardinals; judges and executioners – the shade was an exclusive rite of nobility (as dictated by English Sumptuary Laws, but also by it’s costliness to own). Van Dyck’s portrait of Agostino Pallavicini, the ambassador to the Pope, displays the flowing, luxuriant red cloth associated with his rank. The hue was worn very consciously, as blood red symbolized life and death, martyrdom, forgiveness (evoking the concept of Christ’s atoning blood), as well as power over all over these concepts.

“Item for making of one peire of bodies of crymsen satin,

Item for making two pairs of bodies for petticoats of crymsen satin,

Item for making a pair of bodies for a Verthingall of crymsen satin…”

— from the Clothing Warrants of Mary Tudor

Carmine (Cochineal)

It wasn’t until the introduction of the cochineal (Dactylopius coccus) beetle to Europeans following the Spanish Expedition of South America in 1518, that artists and dyers found the key to the most vivid shades: Carmine red. The kermes could produce a single orangey crimson – but by altering the processes in which they heated the dried cochineal beetles, they could create a range of shades: from scarlets and deep burgundies; to blood-like blue-reds; to gentle, yet lasting blush tones. In addition to the sheer array of stains it made possible, cochineal beetles were more potent in their colorful qualities than kermes – only a tenth of the weight was required to make the same amount of pigment.

Very quickly, the European appetite for this American “red gold” was whetted, and by 1600, the Spanish had exported somewhere between 250,000 and 300,000 pounds of cochineal beetles. By the 18th century, it was exported as far and wide; carmine red began to turn up in all sorts of more “ordinary” places.

For a large portion of the 17th and 18th centuries it was all the rage for both men and women to own carmine red shoes. Louis XIV had limited the wearing of le Talons Rouge to himself and his court, but in the century after his death, the availability and lust for red soon meant that more lowly types were wearing them. The British Army – known to the Americans during the Revolution as “Red Coats” – had their distinctively vivid uniforms dyed with carmine. Many artists also used carmine lake, a pigment harvested from dye-laden scraps of fabric or from the beetle itself, in translucent glazes over renderings of draperies or to add life-like color to skin tones. Sir Joshua Reynolds used carmine lake extensively in his portraiture – though as years passed, this fugitive pigment would fade; the result made the sitters appear to be carved from marble.

“When Sr Joshua Reynolds died

All nature was degraded;

The King dropped a tear into the Queen’s ear;

And all his Pictures Faded.

— William Blake

Here you can see the vividness of the military uniform (that in Reynold’s day would have been dyed in carmine and was most likely painted using synthetic red ochre) remains, as it was likely painted using vermilion; but the flesh tones are colorlessly wan, as the rosy glazes used to tint the under-painting have faded completely. While Joshua Reynolds was the champion of experimenting with new pigments and techniques, modern viewers are ultimately robbed of the life-like sensation of his faded works. Many other groundbreaking artists would have their artistry undone by their testing new red mediums.

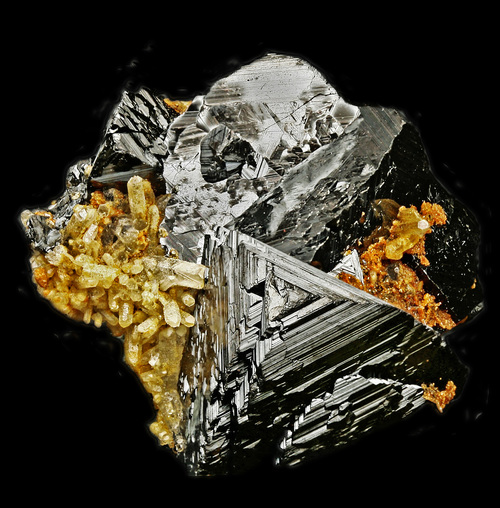

Mars Red

The 19th century saw a synthetic version of an ancient mineral make it’s way to artists’ palettes – chemist-created iron oxides, called Mars red, after the alchemical name for metallic element iron. Mars red was an opaque, brick-tinged red that embodied all of the strengths and permanency of it’s natural counterpart – withstanding exposure to light without loss of tone. It was a favorite of British artists, including John Martin.

The rich red shades used in many of his fantastically apocalyptic paintings, were often symbolic of spiritual evil – a malevolent reputation red has had for eras. The mythos of the medieval bestiaries drew their inspiration from Pliny concerning the procurement of an evil red pigment. The recipe for red pigment described that the dragon’s belly is fully of fire and blood, and that by rupturing his skin, this sanguine shade could be collected by artists. This color was corrupt by nature and was only used specifically for the most vile of renderings: the face of Lucifer, the fires of hell and the punishment of the wicked. While a laboratory is a far cry from the insides of a dragon, the synthetic production of Mars red brought life in the work of Martin, reinforcing the split role that red plays in all our darkest imaginings.

Cadmium

When a German chemist discovered a new colorant in 1817, cadmium red was thought to be the “modern” answer for the dangerous vermilion (cinnabar) that had been in use for thousands of years. Today, we know that cadmium red is also highly toxic formulation of true red, but for artists working with vermilion, something as simple as a cut on the hand or smoking while painting could result in the artist being poisoned. Cadmium red offered a “safer” alternative.

When heated with selenium, cadmium darkens to a rich tint – it’s foremost strengths being it’s opacity and good lightfastness. The only problem with producing cadmium red was locating enough of the rare, metal sulfite mineral greenochite to be produced into the pigment. The scarcity made the red rather costly, meaning that generally artists with more financial means used the color most freely. Cadmium red was a favorite of Matisse, who tried without luck to convert this friend Renoir to cadmium from vermilion. An oldest son from a wealthy family, the extravagant use of the shade reveals that while the paint was costly, Matisse was not the average impoverished artist. It must also be said that Henri Matisse used cadmium red to it’s fullest potential – using it’s thick, opaque qualities to tone entire canvases, toying with the viewer’s sense of perspective.

“A certain blue enters your soul. A certain red has an effect on your blood-pressure.”

— Henri Matisse

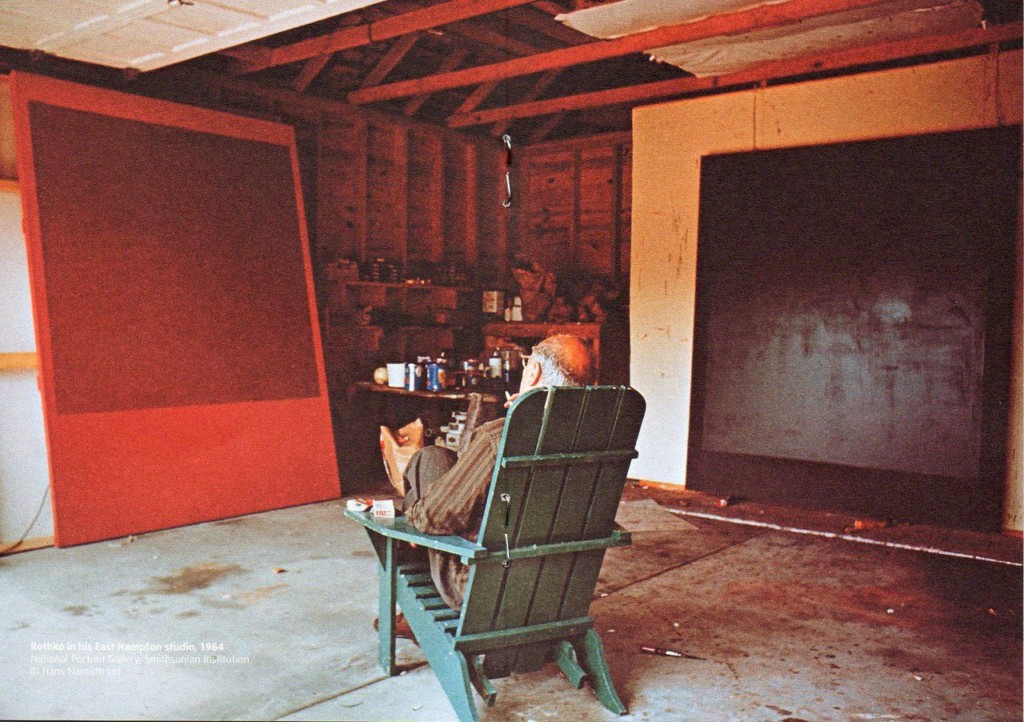

Lithol Red

More modern artists have turned to newer, less fusty sources for their saturated reds – including a synthetic pigment called lithol red. Patented at the end of the 1800’s, lithol red was a cheap, vibrant ink used almost exclusively in industrial paint and printing applications. Artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko experimented with commercial house paints – following a trend seen in mid-20th century that saw artists trying new, untested mediums.

Mark Rothko used lithol red extensively in his late period paintings where massive canvas sizes were stained with the intoxicating bright, clean colors. Rothko used lithol red to cover vast areas in expressive, awe-inspiring sweeps of color. The one disadvantage to Rothko’s pigment of choice is that lithol red is fugitive – it is highly sensitive to light exposure, which makes it to fade to blue. The resulting shift causes the emotive qualities of Rothko’s paintings to be sapped over the course of a few decades – which in turn causes a new sense of urgency for collectors and museums to protect the original integrity of the pieces.

The sense of loosing the vibrancy of red is cause for concern for contemporary art viewers, as we would all like to see the world as vividly as artists in the past have portrayed it. By studying the qualities of fugitive pigments, art conservationists work to take immediate action to preserve the potency of the images we treasure – that the sense of joy or evil, passion or chaos embroiled in the picture plane may not be lost completely. It was not difficult to see why artists are drawn to the complex emotional content of true red, just as we ourselves are captivated by it in turn. In truth our valuation of red is much like that of ancient peoples – we seek it’s permanence, that generations to come may admire humanity’s favorite hue.