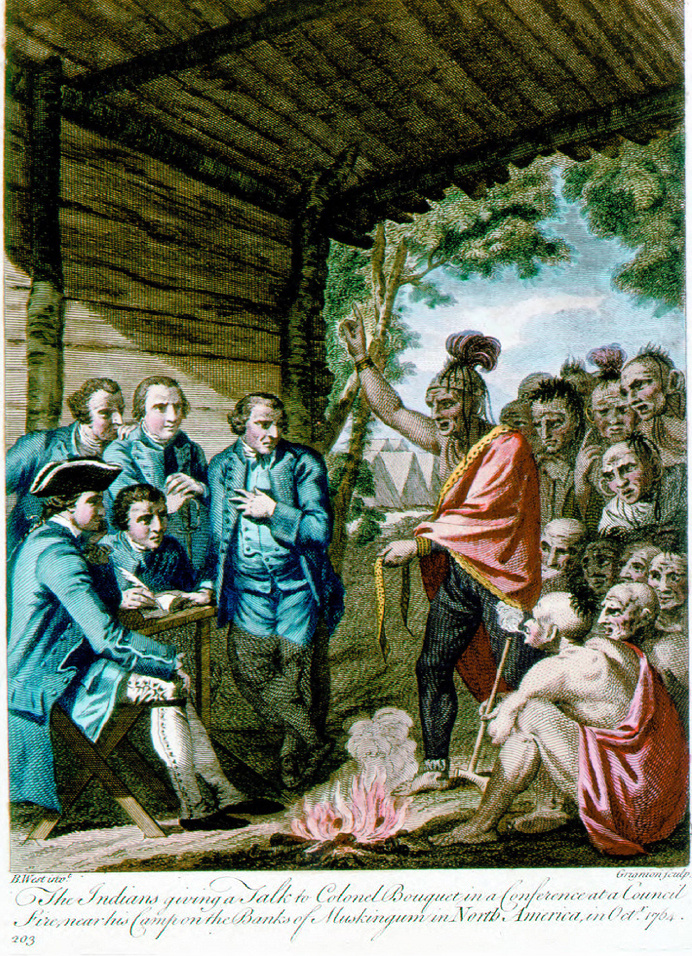

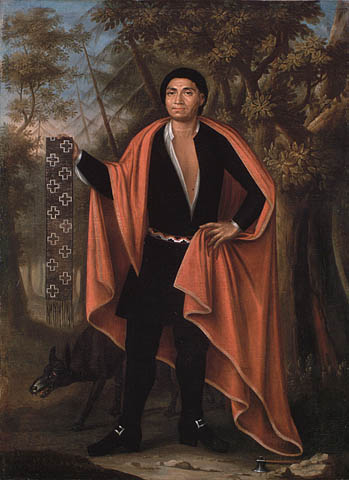

When William Penn first settled in America, his primary task was to establish a peaceful rapport with the Lenape people native to the land. As part of their agreement of friendship, a precious belt of wampum was produced, with figures in purple clasping hands against a background of white; it was a physical reminder of their accordance. George Washington, as a young officer, found himself in possession of one of these shell bead belts – a gift from the French to their Indian allies – and the meaning of the belt was grim. Four houses were laid out in the beads, symbolizing the four posts the native tribe had agreed to defend. Washington would negotiate with the Indians and persuade them to return the belt to the French, in essence dissolving the treaty between them.1 Wampum or wampumpeag, though simple beads woven together with cord, carried enormous significance and played a pivotal role in the alliances and interactions between people throughout it’s history.

In the waters off Cape Cod stretching down through to New York, a variety of mollusk called the quahog is quite plentiful. What is remarkable about this particular clam is that after the meat is removed from the shells, brilliant purple or black striations ring the edges of the shell. To the native people whose lands covered the areas of the Northeastern shores, these shells were considered precious. Through an unfortunate series of events, wampum became recognized as a currency by European colonists and traders and to this day is still wrongfully described as “shell money”.

The Role of Wampum Prior to the Arrival of Europeans

The coastal Algonquin speaking tribes have been making wampum from as early as 2500 BC – this prehistoric form was a flat, disc-like bead. Later, tube shaped wampum would dominate the historic era.

The technique for producing wampum was one that had to be acquired through patience and practice, as the shells were very delicate when they were cut into beads. Using a stone drill called a puckwhegonnautick, was used to bore a hole into each bead for stringing – drilling halfway on one end before flipping the bead to drill the rest of the way. The layers of calcium carbonate that compose the clam’s shell are brittle and while seemingly hard they could shatter into pieces if not worked carefully. Once completed, the wampum was strung on animal sinews or vegetable fibers and made into “belts” of solid beads, often with symbolic designs to record historical events.

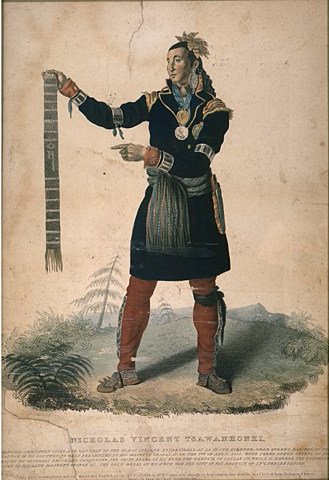

While the idea of making beads suggests that wampum was for jewelry, for natives of the Atlantic shore these beads transcended mere ornamentation. Wampum was used as a means of communication, remembrance, or as a means to bestow honor. Tribes would call each other to meetings by sending a wampum belt. Treaties were made and recorded in wampum, as physical proof of the contract made between parties – cutting up a belt of wampum meant that the treaty was violated or rejected. An exchange of wampum would constitute an engagement between a man and a woman. The dead would be buried with wampum. It was essential for conflict resolutions between individuals – a gift of wampum would turn away the wrath of the wronged party. Wampum also denoted the status of the individuals wearing it within their sachem’s social strata. Belts of wampum recorded historical events.2 Foreigners describe the scenes at some of the great tournaments the Natives played – games that were similar to soccer or rugby that lasted for day – and they mention that enormous numbers of wampum strings were hung upon rafters or posts to be received by the winning team.

The Monetary Worth of Wampum Realized

It was only during an encounter with the Dutch that wampum would take on a sense of monetary value in the eyes of Europeans. In 1622, a trader from the Dutch West Indies Company took a high ranking member of the Pequot sachem hostage, threatening to kill him if a hefty ransom was not received. Over 280 yards of wampum was the ransom deemed appropriate for the status of the captive – to the Dutch trader, it seemed that the most prized possession of the native Americans were shell beads.3 While the reciprocal exchange of the wampum was not capitalistic exchange, the Europeans soon began to use the beads like currency to purchase beaver pelts and other valuable furs.

“After two years of trader persistence, wampum became an item of mass consumption, and Plymouth had effectively eliminated most of its small-scale competitors.… [Once] a symbol of prestige, wampum had become a medium of exchange and communication available to all, leading Indians through-out New England toward greater dependence on their ties with Europeans.”

— Neal Salisbury – Manitou and Providence

The Power Struggles Behind Mass Production Of Wampum

The Dutch encouraged tribes to devote themselves solely to the production of wampum (called Zeewant in Dutch) so the Pequot and the Narragansett tribes busied themselves with the manufacture of what would be known for centuries following as “Indian money”. Tribes that were left out of this monopoly on wampum production would pay tribute to the more influential tribes, to keep their alliances strong and ensure their protection. Later, the tensions and power struggles between English and Dutch colonies and these two influential tribes producing wampum would result in the Pequot War, where the main wampum production or wampum storage villages were targeted and the entire Pequot tribe would be destroyed. With the Pequots being removed from the trade, the Narragansetts gladly stepped into the void left in the market.

Wampum was considered legal tender from 1637 to 1661 (and even up through the 1670’s in some colonies) with a set exchange rate against the Dutch stuiver.

— Daniel Gookin, Massachusetts missionary to the Wamponoag

… It answers all occasions, as gold and silver doth with us.

This wampum’s value as currency realized, the culture behind the production of the beads altered. The Dutch were already using Venetian glass beads for trading with other indigenous peoples they interacted with in Africa and India, and the natives living in North America were amiable to innovative products, to the idea of acquiring new spiritual power and to engaging socially and making alliances with newcomers, expecting that there would be balance and reciprocity as it existed within their own culture. In some wampum belts, glass beads are mixed with authentic shell beads as part of a repair – or simply used as interchangeable in meaning and power with the shell beads.

Wampum Looses Monetary Status

A change that took effect when wampum was used as currency is one that most everyone familiar with minted currencies: counterfeit.4 The rates for beads were based on their rarity – the white beads begin most prevalence and least costly, the purple being rarer and more costly and the black beads being the rarest and highest in rate of exchange. The temptation to dye inexpensive white beads with black dye to pass them off as more expensive black beads was too much for some enterprising souls, so the market was flooded with counterfeit currency. Laws were passed to try to curb the influx of counterfeit wampum, stating: “All wampum was to be strung in uniform units of one, three, and twelve pence in white and blacke at values of a pence 6 pence, 2 shillings 6, and 10 shillings…

“5 Connecticut ordered that “no peaque, white or blacke, be paid or received but what is strung in some measure, suitably, and not small. great. uncomely. or disorderly mixt, as formerly it hath been.

“6

Around this same time, the lucrative business of the American fur trade died down as the West Indies imports of sugar, molasses, indigo, tobacco and cloth became highly profitable – as was the timber exported from the colonies for shipbuilding. Minted silver coins were being used in exchange for goods in the islands, and in the 1650’s they ended up in the American colonies as well. The Massachusetts Bay Company set up a mint in Boston, and began producing their own coinage, the Boston or Bay Shilling. The sudden abundance of coin and the shifting market demands caused wampum to become obsolete as a legal tender. In 1661, the wampum valuation laws were repealed and wampum would no longer have a set exchange rate, only that agreed on by the parties involved in the transaction. Tribes like the Narragansetts, who had focused their communal efforts so completely on the production of wampum, would find they had no other enterprise to fall back on. While the once precious shell beads were still made in following years, their ancient spiritual and communicative powers remained somewhat undermined and their monetary value was completely diminished.

Sources:

- Farabee, Wm. C.. “A Newly Acquired Wampum Belt.” The Museum Journal XI, no. 1 (March, 1920): 77-80. Accessed June 07, 2022. https://www.penn.museum/sites/journal/769/

- “Wampum.” Onondaga Nation, 27 Jan. 2021, https://www.onondaganation.org/culture/wampum/

- Tweedy, Ann C. “From Beads to Bounty: How Wampum Became America’s First Currency-and Lost Its Power.” Indian Country Today, Indian Country Today, 5 Oct. 2017, https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/from-beads-to-bounty-how-wampum-became-americas-first-currencyand-lost-its-power.

- Lynch, Jack. “The Golden Age of Counterfeiting: Cashing in on Colonial Currency.” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/Summer07/counterfeit.cfm.

- Scozzari, Lois. “The Significance of Wampum to Seventeenth Century Indians in New England.” Hartford Web Publishing, https://www.wampumbear.com/P_Significance%20of%20Wampum.html

- Scozzari, Lois. “The Significance of Wampum to Seventeenth Century Indians in New England.” Hartford Web Publishing, https://www.wampumbear.com/P_Significance%20of%20Wampum.html

brianstammVerified

Interesting article. I was under the impression that beads in various colors were also made from small bones and stones for Wampum. Learned something new today.